Good mood gone bad

A burst of happiness may impair children’s attention to detail

Normal 0 false false false MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

Happy children learn especially well, unless they have to focus on details rather than the big picture. That’s the implication of a new study in which school-age youngsters induced to feel happy lagged behind their sad- or neutral-feeling peers in finding shapes embedded within larger images.

This two-part investigation shows for the first time that an experimentally induced good mood undermines children’s ability to perform detail-oriented tasks, report psychologist Simone Schnall of the University of Plymouth in England and her colleagues online and in an upcoming Developmental Science.

Earlier studies had indicated that a surge of happiness draws adults’ attention away from the details of a problem but increases both adults’ and children’s creativity and mental flexibility.

Schnall hypothesized that positive and negative feelings evolved, in part, to trigger contrasting thinking styles. Happiness signals a sense of personal safety that encourages a relaxed, broad focus on one’s immediate situation. Sadness reflects awareness of a difficult problem or situation, prompting caution and a detailed surveillance of one’s surroundings.

Psychologist Joseph Forgas of the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, supports Schnall’s scenario. “There is now clear experimental evidence showing that mild sadness produces cognitive advantages in performing tasks that require attention to detail and focusing on new information,” Forgas says.

Psychologist Alice Isen of CornellUniversity disagrees. She regards the emotion-inducing methods and cognitive tests employed by Schnall and other researchers as inadequate to confirm a cognitive downside to happiness.

Earlier studies, such as one in which Isen and her colleagues studied physicians making diagnostic decisions, indicate that people induced to feel happy alternate skillfully between monitoring detailed information and thinking more expansively, depending on situational demands.

In contrast, studies conducted by Forgas indicate that mildly sad adults do better than mildly happy ones on detail-oriented tests of social judgments, eyewitness memory and the ability to present persuasive arguments on controversial topics.

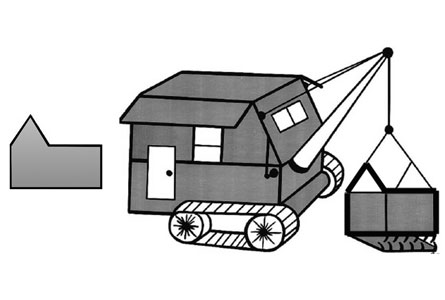

In one experiment, Schnall and her coworkers tested 30 children, ages 10 and 11, while either lively or gloomy pieces of classical music played in the background. Each child completed 20 problems requiring that he or she locate either a triangle or a houselike shape in a larger, more complex figure.

Children listening to lively music then communicated how they felt by pointing to a drawing of a happy face, whereas those listening to gloomy music selected a drawing of a sad face. Youngsters chose from five faces, ranging from happy to neutral to sad.

Compared with sad kids, happy ones consistently took at least one second longer to find embedded shapes, and correctly identified an average of three or four fewer shapes.

In a second experiment, the researchers addressed whether happiness impaired children’s ability to find embedded shapes, or whether sadness enhanced it. They tested 61 children, ages 6 and 7, on the same embedded shape problems. Each child first watched either a happy scene, a neutral scene, or a sad scene from one of three animated feature films. Participants reported how they felt by pointing to face drawings consistent with the emotional tone of just-viewed film clips.

Children who felt sad or neutral did equally well at identifying embedded figures, correctly solving an average of two to three more problems than happy kids did.

In other words, sadness did not elevate performance over that achieved with a neutral mood, but happiness worsened performance.

Cornell’s Isen sees serious flaws in the new study. Lively music can arouse or distract individuals more than gloomy music does, possibly harming the ability to find embedded figures, she says. And embedded figures provide a poor measure of attention to fine details, in her view.

This scientific debate raises the question of why sadness exists at all, Forgas says. “If sadness has no benefit, why is it so ubiquitous?” he asks.