The great Pacific garbage patch may be 16 times as massive as we thought

New estimates put greater weight on larger plastics

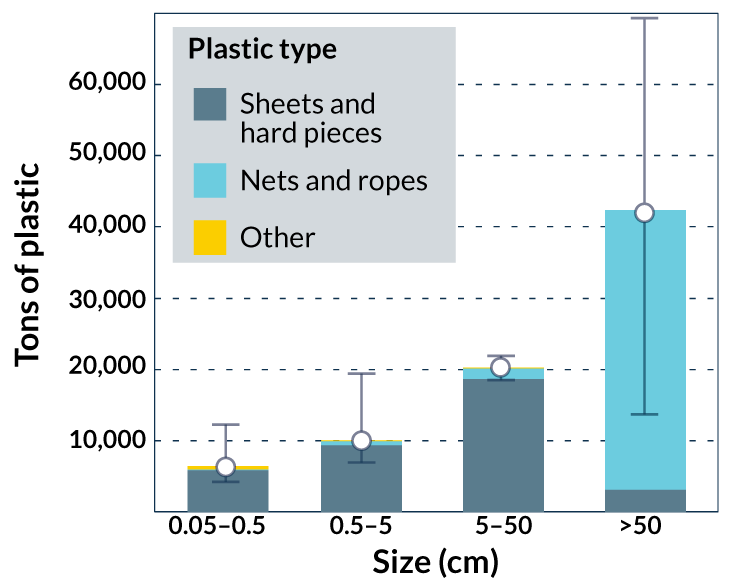

THINGAMABOBS Fishing nets and ropes make up 47 percent of the plastic mass in the Pacific Ocean’s notorious garbage patch, a new study suggests.

NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Program/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)