Extra fingers, often seen as useless, can offer major dexterity advantages

An extra digit proves useful for texting, typing and eating, a case study shows

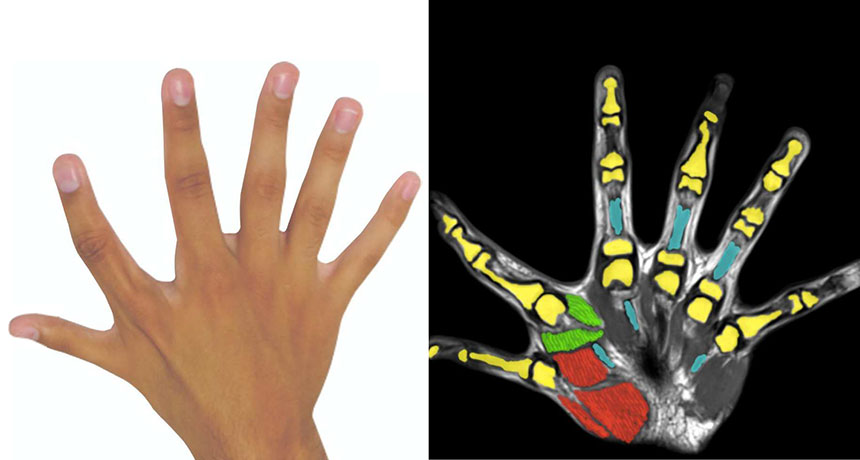

ALL TOGETHER NOW An extra finger on the right hand of a 17-year-old boy is controlled by its own muscles (red and green) and tendons (blue; bones are shown in yellow).

C. Mehring et al/Nature Communications 2019