The data capacity of a computer’s magnetic hard drive depends largely on the sensitivity of a detector, or read head, that’s used to decipher its contents. Scientists have now exploited a method for detecting the orientations of magnetic fields to achieve a remarkable leap in sensitivity.

In the surface of a hard drive’s spinning disk lie tiny magnetized regions, or domains, whose magnetic field orientations represent either a 1 or a 0. As domains pass beneath it, a head responds to the changes in the magnetic field orientations with variations in its electrical resistance.

In today’s read heads, a domain’s passage creates about a 15 percent change in electrical resistance. In experiments on a new prototype detector, Harsh D. Chopra and Susan Z. Hua of the State University of New York at Buffalo have measured a 33-fold resistance change.

Current hard drives store magnetic data at about 20 billion bits per square inch, but the newly reported jump in resistance could lead to storage densities that surpass a trillion bits per square inch, Chopra claims. However, this would also require improvements in write heads that record data by magnetizing the disk’s domains, he notes.

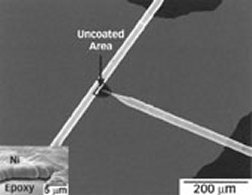

In their setup, the Buffalo scientists glued two hair-thin nickel wires in a T arrangement on a glass surface. Into a tiny gap between the shaft of the T and its crossbar, the researchers electrochemically deposited a few hundred nickel atoms.

Both wires just touched the nickel blob to create a so-called nanocontact. Such structures respond to changing magnetic fields with steep changes in resistance.

This type of magnetoresistance is called ballistic because the electrons’ paths are so short that the particles don’t collide with atoms as they zip through the nanocontact.

While imposing magnetic orientations on the wires, the researchers passed electrons, which also have magnetic orientations, through the wires and the nanocontact. When the wires’ magnetic orientations matched, electrical resistance in the circuit was low, but it soared when the magnetic orientations were different, Chopra and Hua report in the July 1 Physical Review B.

In their experiment, Chopra and Hua duplicated a technique invented in 1999 by Nicols García of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas in Madrid. Last December, García reported an eight-fold resistance change in a similar two-wire structure. However, the Buffalo team went further by sharpening one wire to a much finer point than García did. This resulted in a more precise contact between the point and the blob. This difference may have led to the dramatic leap in resistance, Chopra says.

“They did a nice job of tapering the contact,” comments Stuart A. Solin of the NEC Research Institute in Princeton, N.J. However, because of possible problems, such as electrical noise in the nanocontact, he doubts that the technique will prove practical.

William F. Egelhoff Jr. of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md., lauds the new work as “a big discovery, a big advance.” What’s most impressive about it, he says, is that the data collected by the Buffalo researchers indicate that even larger resistance changes may be possible.