Highlights from annual meeting of infectious disease specialists

Heartburn pills increase risk of pneumonia, a better catheter and more presented October 2-6, 2013 at ID Week in San Francisco

Heartburn pills linked to higher pneumonia risk

Proton pump inhibitors, the acid-blocking drugs that many people take for acid reflux disease, may increase a person’s risk of pneumonia by half.

When researchers pooled results from 21 studies of people taking PPIs or not, they found the risk of pneumonia in those exposed to the drugs was 1.49 times that of people who didn’t take the drugs. The greatest effect showed up in the first month of use, when the risk of pneumonia doubled in people on PPIs. Those drugs include Nexium and Prilosec.

Analyses of other studies of people taking other heartburn drugs such as Zantac showed no increased risk of pneumonia, said Trevor Crowell, an infectious disease physician at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, on October 4.

The study doesn’t prove that PPIs cause pneumonia, but the association is substantial, he said. “One hypothesis is that stomach acid limits bacterial growth,” Crowell said. By reducing stomach acid, PPIs may allow bacteria to grow and inevitably float up the esophagus and into the lungs, increasing pneumonia risk. Drugs such as Zantac are shorter-acting, less potent and reduce acid by a different mechanism.

Many people stay on PPIs indefinitely without necessarily having gastroesophageal reflux disease (SN: 12/4/10, p. 30). Doctors should limit PPI prescriptions to those in need, Crowell said.

Healthcare workers look to bosses on flu vaccination

Healthcare workers are more likely to get a flu shot if their supervisors do, psychologist Kim Corace of Ottawa Hospital in Canada found in a survey.

While healthcare staff may seem likely to get the annual shots consistently, that’s not the case. Only about half of Ottawa Hospital staff got vaccinated in the relatively routine flu season spanning late 2008 and early 2009. During the pandemic flu season of 2009-2010, the fraction rose to just 70 to 80 percent, she reported on October 3.

Corace also presented data based on questionnaires filled out by 3,275 healthcare workers. The most common reason why workers chose not to get shots was that they felt healthy and didn’t perceive themselves as susceptible to flu, she found. The second-most common reason was concern over vaccine safety.

People who got the flu shot said most often that they did so to protect their own health. Other popular responses were protecting their families’ health and their patients’. Many pointed out one additional factor. “If colleagues and supervisors were pro-vaccination in the workplace,” Corace said, “the workers were more likely to follow suit.”

Shark-inspired catheters less hospitable to microbes

Taking a tip – and a name – from sleek creatures of the deep, researchers at Sharklet Technologies in Aurora, Colo., have designed a catheter coating that might inhibit common infections in hospitals.

Catheters are polyurethane tubes that carry fluids in and out of patients. Although sterile when inserted, catheters that stay in patients for days or weeks can get colonized by biofilm-forming bacteria.

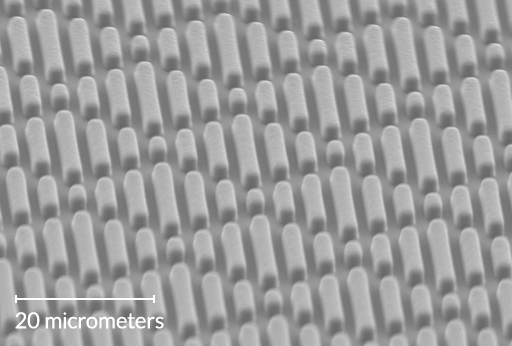

To design a catheter more impervious to microbes, Rhea May, a microbiologist at Sharklet, looked to earlier research that had revealed unique diamond-shaped patterns on sharks’ skin. “They don’t accumulate microbial growth, algae or barnacles,” May said. She then created textured polyurethane with a shark-like micropattern molded onto it.

On October 3, she presented results of tests of the polyurethane material when immersed in blood or saline and then exposed to the troublesome bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. Compared with standard catheter material, the new material allowed just 20 to 40 percent as much staph bacteria to attach, the study showed.

“Our hope is that when you have this sort of reduction [in bacterial adherence] and don’t allow for biofilm formation, that our bodies can keep up with the infections and clear them,” May said.