Here’s how graphene could make future electronics superfast

The single layer of carbon atoms can boost signals from gigahertz to terahertz frequencies

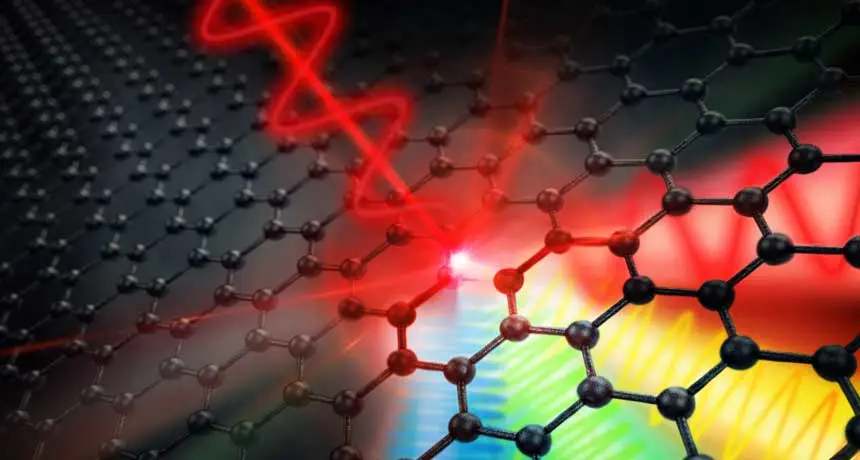

SPECTRAL SPECTACLE New experiments show that graphene is especially good at translating incoming signals of one frequency (illustrated in red) into signals of higher frequencies (yellow, green and blue).

Juniks/HZDR

Graphene just added another badge to its supermaterial sash.

New experiments show that this single layer of carbon atoms can transform electronic signals at gigahertz frequencies into higher-frequency terahertz signals — which can shuttle up to 1,000 times as much information per second.

Electromagnetic waves in the terahertz range are notoriously difficult to create, and conventional silicon-based electronics have trouble handling such high-frequency signals (SN: 3/28/09, p. 24). But graphene-based devices could. These future electronics would work much faster than today’s devices, researchers report online September 10 in Nature.

Physicist Dmitry Turchinovich of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany and colleagues tested graphene’s terahertz-producing prowess by injecting a sheet of this atom-thick material with 300-gigahertz radiation. When these electromagnetic waves hit the graphene, electrons in the material rapidly heated and cooled off, releasing electromagnetic waves with frequencies up to seven times as high as the incoming radiation.“This is yet another amazing result for graphene,” says Orad Reshef, a physicist at the University of Ottawa not involved in the work. The 2-D material has been hailed as a supermaterial for its extraordinary abilities, such as conducting electric current with no resistance (SN: 3/31/18, p. 13).

The graphene converted more than a thousandth, a ten-thousandth and a hundred-thousandth of the original 300-gigahertz signal into waves at 0.9, 1.5 and 2.1 terahertz, respectively. That conversion rate may seem small, but it’s remarkably high for a lone layer of atoms, says Tsuneyuki Ozaki, a physicist at the National Institute of Scientific Research in Quebec City not involved in the work.

Graphene-based computer components that can deal in terahertz “could be used, not in a normal Macintosh or PC, but perhaps in very advanced computers with high processing rates,” Ozaki says. This 2-D material could also be used to make extremely high-speed nanodevices, he adds.