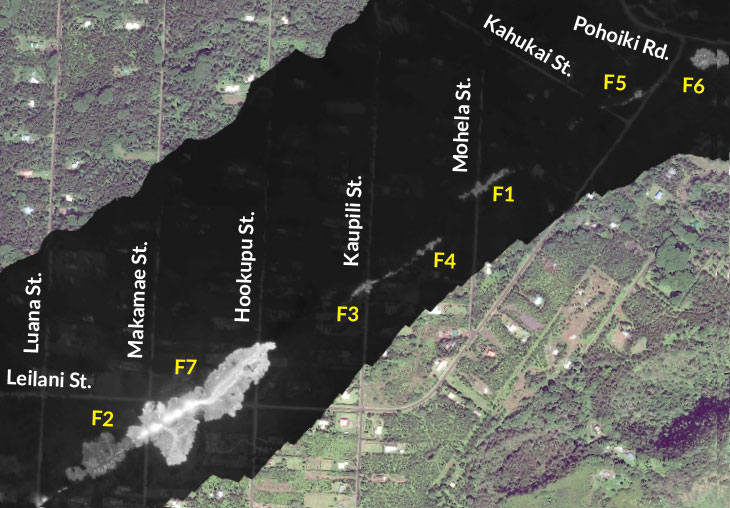

CREEPING FIRE Lava flowing from new fissures along the eastern flank of Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano engulfed part of Makamae Street in a housing subdivision on May 6.

U.S. Geological Survey

Cracks open in the ground. Lava creeps across roads, swallowing cars and homes. Fountains of molten rock shoot up to 70 meters high, catching treetops on fire.

After a month of rumbling warning signs, Kilauea, Hawaii’s most active volcano, began a new phase of eruption last week. The volcano spewed clouds of steam and ash into the air on May 3, and lava gushed through several new rifts on the volcano’s eastern slope. Threatened by clouds of toxic sulfur dioxide–laden gas that also burst from the rifts, about 1,700 residents of a housing subdivision called Leilani Estates were forced to flee their homes, which sat directly in the path of the encroaching lava.

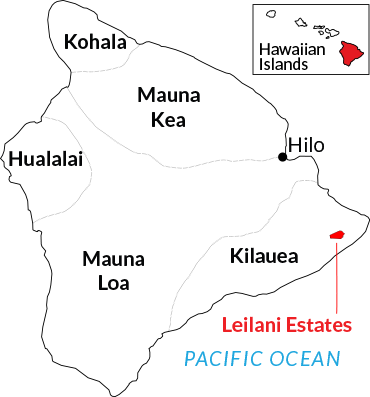

The event marks the 62nd eruption episode along Kilauea’s eastern flank, which is really part of an ongoing volcanic eruption that started in 1983. The volcano is one of six that formed Hawaii’s Big Island over the past million years. Mauna Loa is the largest and most central; Kilauea, Mauna Kea, Hualalai and Kohala occupy the island’s edges. Mahukona is currently submerged. All six are shield volcanoes, with broad flanks composed of hardened lava flows.

Kilauea’s activity has now shifted to its southeast flank, which continues to steam. No new rifts have opened since May 7, but the eruption may be far from over, says Victoria Avery, a volcanologist and associate program coordinator for the U.S. Geological Survey’s Volcano Hazards Program, based in Reston, Va.

OF SOUND AND FURY Watch scenes of Kilauea’s fiery eruption, which has engulfed homes, roads and cars and forced the evacuation of thousands of people in Hawaii. |

Science News talked with Avery about Kilauea’s fury, the quakes and what to expect next from the volcano. Her responses were edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Is there anything unusual about this eruption?

A: Not to scientists; it’s typical of what Kilauea volcano can do.

Q: Were there any warning signs?

A: We saw shallow earthquake activity under [the eastern flank of Kilauea] for several days. That tells us that molten rock is moving underground. We also saw that the lava lake at the summit of Kilauea was lowering; there’s a vent called Pu’u ‘O’o [which has erupted nearly continuously since 1983], and the floor [beneath its magma reservoir] collapsed on April 30. That told us that magma is being withdrawn and moved elsewhere. That collapse, plus the new seismicity, told us something was going to happen.

Q. On May 4, two large earthquakes measuring magnitude 5.4 and magnitude 6.9 shook the Big Island in quick succession. How are they related to the eruption?

A: It’s not frequent but not unusual for Hawaii to have earthquake[s] like that, because a volcano is a very dynamic place. The [surface swelling] associated with the eruption probably triggered the quake[s]: The magma pushed on the volcano from inside. The whole south flank of Kilauea is an area that has a history of large earthquakes. We didn’t directly anticipate it, but we weren’t that surprised when it happened.

Q: Did the people who live there know they were in a hazardous zone?

A: The eruption is right on one of the rift zones of the volcano. The fact that there was a subdivision right on top of it, I can’t comment on. But those houses are right where we know it can erupt. Right now, [emergency managers] are allowing people back in briefly to check on their homes, but not allowing them to stay.

Q: How dangerous is the gas that’s also erupting with the lava?

A: The gas is chiefly carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide. The gas is actually what propels the [lava] to come out of the ground. Carbon dioxide in enough quantity can suffocate people. Sulfur dioxide can react with the atmosphere to create sulfuric acid. It forms “vog,” or volcanic fog, that can exacerbate asthma. That’s why they’re putting gas masks on people who go in to check on their homes.

Q: How are researchers monitoring this eruption?

A: We’re using the classic tools: instruments measuring seismicity and deformation, visual observations on the ground or flying over in helicopters, and thermal and deformation imagery from satellites. Using remote sensing, you can take [high-resolution images of ground elevation using] synthetic-aperture radar, or SAR, measurements at two different points in time to see the deformation.

Hawaii is a supersite, which means we get a lot of free SAR imagery over it, at about every two or three days. That may not be enough time for frequent eruption warnings, but it’s useful to monitor precursor activity and know what to look for. In the future, we’d like to use drones as well to monitor the eruptions.

Q: Nearby Mauna Loa is on yellow alert (to inform the aviation sector of potential ash hazards), because the volcano is showing signs of unrest. Is it at risk of erupting, too?

A: Mauna Loa really scares us. It is the largest volcano on the planet; it’s the big monster volcano of Hawaii. Kilauea has been erupting continuously since 1983, but Mauna Loa last erupted in 1984. But Mauna Loa can pump out much larger volumes and much faster. It has been yellow since September 2015, when there was elevated seismicity and deformation. It’s still a yellow, but it has quieted a bit.

Q: What’s next? Does the lull in activity at Kilauea mean the eruption is almost over?

A: It’s likely only a pause. The seismicity and deformation can wane and then build up again. The best we can do is watch precursor phenomena 24/7. [These include] the seismic data, the height of the lava lake and the deformation of the volcano along the rift zone. Where it swells, the magma is underneath it; where it goes down, the magma is withdrawing.

Q: The lava lake appears to be sinking again (as of May 6). Does that suggest more eruption is imminent?

A: It generally means that the lava is traveling down the rift zone. There’s likely more to come.

Editor’s note: This story was updated May 16, 2018, to correct the location of the eruptions.