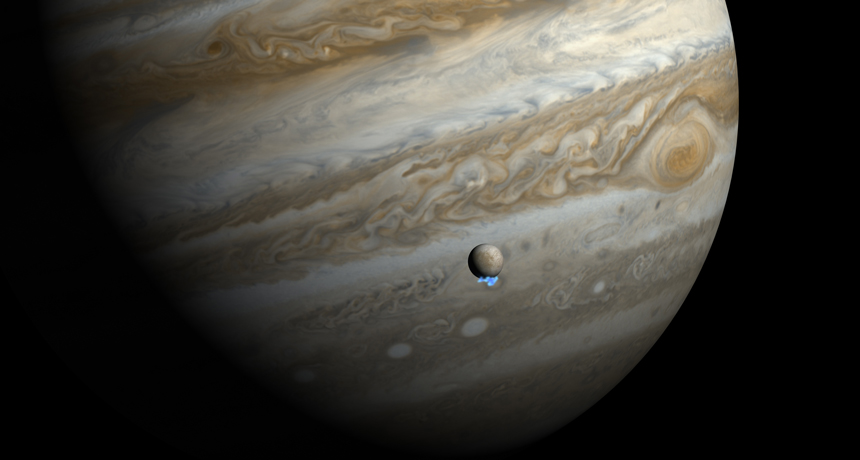

Hubble telescope ramps up search for Europa’s watery plumes

Observations in the next 8 months aim to confirm that Jupiter’s icy moon spews water from its south pole

LITTLE MOON, BIG WORLD Watching the tiny ice moon Europa cross in front of Jupiter helped astronomers reveal Europa’s watery plumes. This artist’s impression superimposes real visible images of Jupiter and Europa with ultraviolet data from the Hubble Space Telescope showing the plumes (blue).

NASA, ESA, and M. Kornmesser