Humanity’s upright gait may have roots in trees

A new analysis of apes’ wrist bones suggests that a two-legged stride evolved from tree climbing, not ground-based knuckle-walking

Chimpanzees don’t knuckle under like gorillas, and that may explain how people ended up walking on two legs, a new study suggests.

Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthopology in Leipzig, Germany, and Daniel Schmitt of Duke University in Durham, N.C., find a new explanation for a set of wrist-bone traits traditionally thought to signal knuckle-walking on flat surfaces by modern apes and ancient hominids — members of the human evolutionary family. These wrist traits actually reflect two types of knuckle-walking that evolved independently in gorillas and chimps, the researchers say.

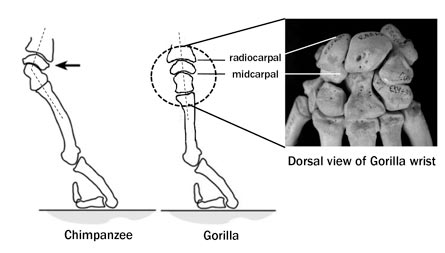

Modern chimps and gorillas both walk on their knuckles, but in different ways. Chimps walk flexibly with bent wrists, giving them added stability on tree branches but putting substantial stress on angled wrist joints, the anthropologists report in a paper published online Aug. 10 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. As a result, chimps’ wrist bones include tiny ridges and depressions that keep their wrists from bending too far.

Gorillas stride with arms and wrists extended straight down and locked in an elephant-like stance, the scientists say. This puts minimal stress on gorillas’ forelimb bones, which are stacked one on top of another. Consequently, their wrist bones display no modifications for stabilization during movement, the scientists assert.

Wrist bones of hominids, including human ancestors, that lived more than 3 million years ago resemble those of chimps, according to Kivell and Schmitt. That’s consistent with the notion that hominids’ upright stance evolved from a common ancestor of African apes that scuttled through the trees using all four limbs and sometimes walked upright (SN: 8/4/07, p. 72), they propose.

“Our data show that there is no unequivocal evidence for a terrestrial, knuckle-walking phase in human evolution and provide strong support for a human evolutionary history in the trees,” Kivell says.

Kivell and Schmitt convincingly show that the anatomy of knuckle-walking differs in chimps and gorillas, remarks anthropologist Susannah Thorpe of the University of Birmingham, England. Hominids retained the anatomical basis of an upright stance from a tree-dwelling great ape ancestor, Thorpe proposes.

Other researchers disagree. Key wrist traits in early hominids for knuckle-walking on the ground, such as a mechanism for locking the wrist in place, were not considered in the new study, says anthropologist Brian Richmond of George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Humanity’s upright stance evolved from an ancestor capable of knuckle-walking on the ground and in the trees, he hypothesizes.

African apes, humans and fossil hominids all display a fusion of two wrist bones that may, despite the new findings, derive from an ancestor capable of terrestrial knuckle-walking, adds anthropologist Matthew Tocheri of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Kivell and Schmitt compared juvenile and adult wrist bones of 147 common and pygmy chimps with comparable bones from 91 gorillas. The researchers also looked at a set of wrist bones from 43 nonknuckle-walking, African monkeys, belonging to species that lived either in the trees on the ground.

Two key wrist features thought to be associated with stabilizing the wrist for knuckle-walking on the ground appeared in only a handful of gorillas but in a large majority of chimps, the researchers say. One or both wrist features were also present in a majority of monkeys.

Five other wrist traits commonly attributed to knuckle-walking on the ground also showed no relationship to that behavior in the African ape and monkey sample. “Our evidence clearly demonstrates a surprising amount of anatomical variation between gorillas and chimps that scientists did not fully recognize before,” Kivell says.