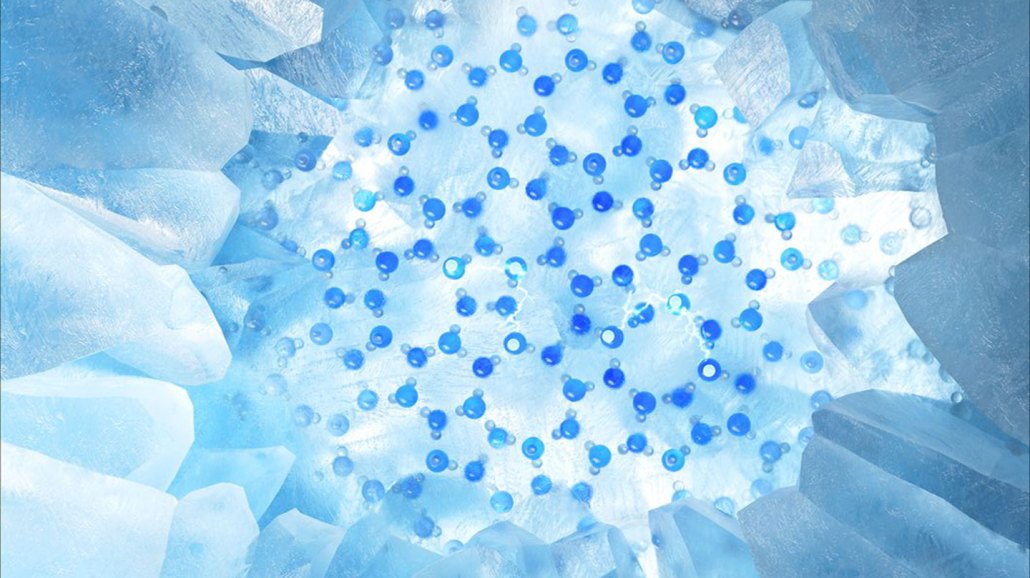

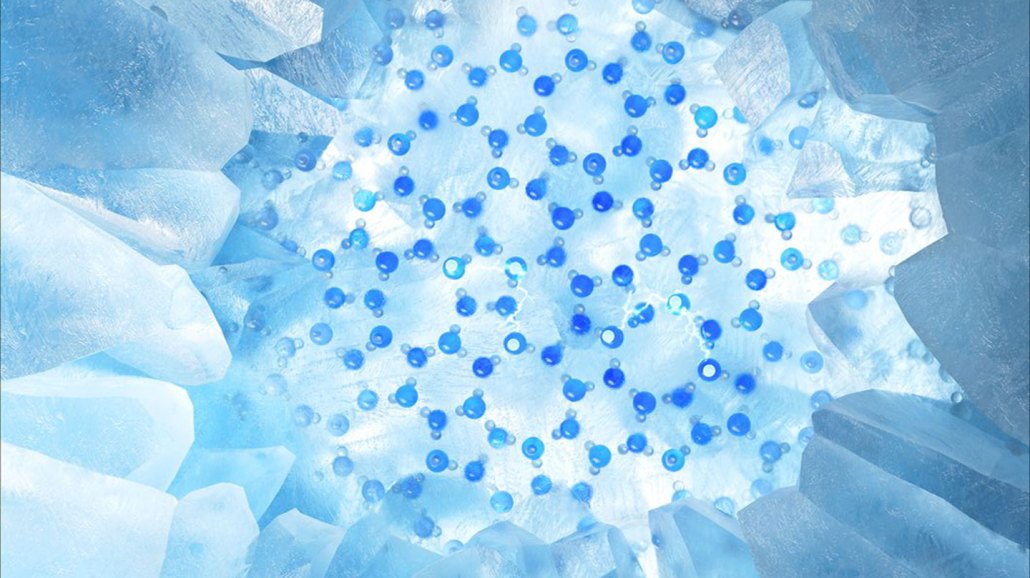

Frozen water’s slipperiness comes from a liquidlike layer on its surface. Arrangements of water molecules on the surface of ice (illustrated in blue) are helping to explain how that layer forms.

Jiang group/Peking University

Frozen water’s slipperiness comes from a liquidlike layer on its surface. Arrangements of water molecules on the surface of ice (illustrated in blue) are helping to explain how that layer forms.

Jiang group/Peking University