Scientists created a new form of ice by shaking 1-centimeter-wide stainless steel balls together with standard ice (shown) at low temperature. The new ice has a density close to commonplace liquid water.

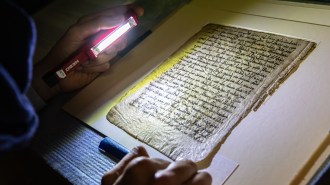

Christoph Salzmann

Ice cubes float in water because they’re less dense than the liquid. But a newfound type of ice has a density nearly equal to what’s in your water glass, researchers report in the Feb. 3 Science. If you could plop this ice in your cup without it melting immediately, it would bob around, neither floating nor sinking.

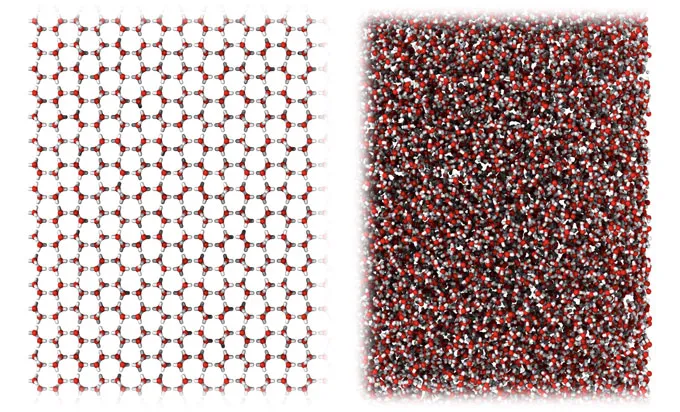

The new ice is a special type called an amorphous ice. That means the water molecules within it aren’t arranged in a neat pattern, as in normal, crystalline ice. Other types of amorphous ice are already known, but they have densities either lower or higher than water’s density under standard conditions. Some scientists hope this newly made amorphous ice could help solve the scientific mysteries that swirl around water.

To generate the new ice, scientists used a surprisingly simple technique. Called ball milling, it involves shaking a container of ice and stainless steel balls, cooled to 77 kelvins (nearly –200° Celsius). The researchers were motivated by curiosity; they didn’t expect the technique to produce a new amorphous ice. “It was a sort of Friday-afternoon idea we had, to just give it a go and see what happens,” says physical chemist Christoph Salzmann of University College London.

An analysis of how X-rays scattered from the frosty stuff suggested they’d created an amorphous ice. And computer simulations that mimicked the effects of ball milling revealed that a disordered structure could be produced by layers of ice sliding past one another in random directions, in response to the forces exerted by the balls.

“You have to be open, as a scientist, for the unexpected,” says chemical physicist Anders Nilsson of Stockholm University, who was not involved with the research. The ball milling technique, he says, “was quite innovative to do.”

Since the material was made by mashing up normal ice, its relationship to liquid water is unknown. It’s unclear whether it can be produced directly, by cooling liquid water. Not all amorphous ices share this connection with their liquid state.

If the new ice does have this link to the liquid, the ice might help scientists better understand water’s quirks. Water is puzzling because it flouts the norms for liquids. For example, whereas most liquids become denser upon cooling, water gets denser as it gets closer to 4° C, but becomes less dense as it is cooled further.

Many scientists suspect water’s weirdness is connected to its behavior as a supercooled liquid (SN: 9/28/20). Pure water can remain a liquid at temperatures well below freezing. Under such conditions, liquid water is thought to exist in two different phases, a high-density liquid and a low-density one, and that dual nature could explain water’s behavior under more typical conditions (SN: 11/19/20). But much remains uncertain about that idea.

Salzmann and colleagues suggest that the new ice could be a special form of water called a glass. Glasses can be made by cooling a liquid quickly enough that the molecules can’t rearrange into a crystal structure. The glass in a windowpane is an example of this kind of material, made by cooling molten silica sand, but other substances can form glasses, too.

If the new ice is a glass state of water, scientists would need to work out how it fits into that dual-liquid picture. And that could help scientists tease out what’s really going on at difficult-to-study supercooled conditions.

But some researchers are skeptical that the new material has any connection to the weird physics of liquid water. Physical chemist Thomas Loerting of the University of Innsbruck in Austria thinks that the ice is “closely related to very small, distorted ice crystals,” rather than the liquid form of water.

Still, earlier computer simulations have suggested that water could form glasses of a range of densities close to liquid water, says computational physicist Nicolas Giovambattista of Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. Those simulations produced structures similar to the ones seen in the computer simulation of ball milling ice, says Giovambattista, who was not involved with the new research. “It opens doors for new questions. It’s new, so what is it?”