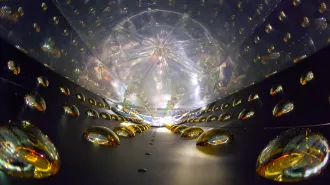

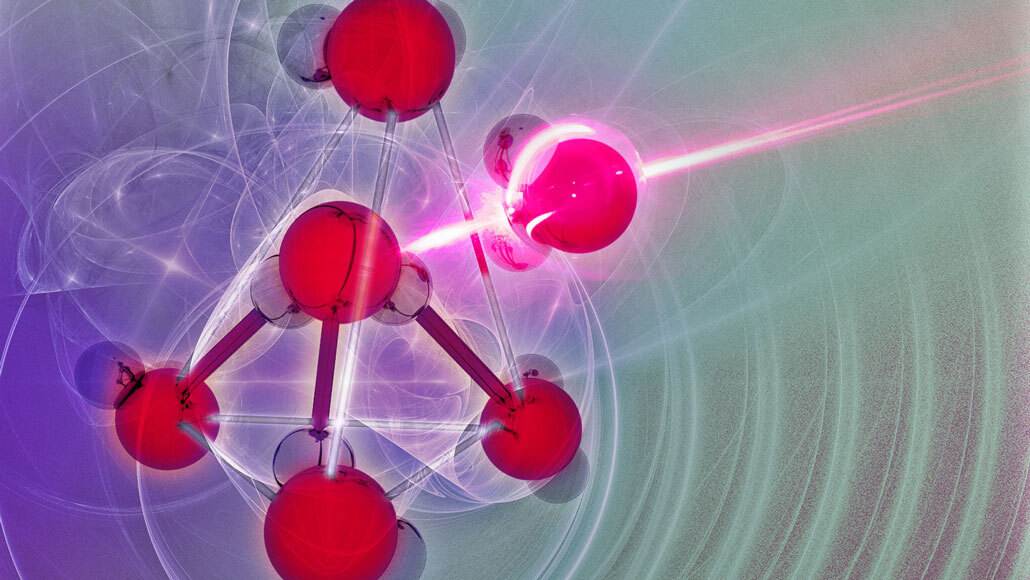

Liquid water cooled to very low temperatures has high-density and low-density arrangements of molecules, a new study suggests. The high-density structure is illustrated here with molecules containing oxygen atoms (red spheres) and hydrogen atoms (silver spheres).

Timothy Holland/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory