Life’s Housing May Come from Space

Gimme shelter! The cell-like envelopes in which life on Earth arose and evolved may literally have dropped from the sky, a new study suggests.

Scientists exploring the origins of life have focused on two ingredients—proteins, the workhouse molecules that underlie life’s activities, and DNA, the molecule that carries the blueprint for future generations. But to thrive, life as we know it requires something else: a container to protect the molecular machinery from the vagaries of the world around it.

Icy materials present in gas clouds throughout our galaxy could have provided this shelter, according to researchers from NASA’s Ames Research Center, SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif., and the University of California, Santa Cruz. The materials could have hitched a ride to Earth on comets, meteorites, or interplanetary dust.

In their lab, the scientists prepared wafers of a frozen mix containing water, methanol, ammonia, carbon monoxide, and other molecules known to be present in interstellar gas clouds. They then subjected the wafers to the frigid temperatures and high vacuum present in deep space. Next, they zapped the ices with ultraviolet light for several weeks, mimicking the high-energy radiation that these molecules would receive in space.

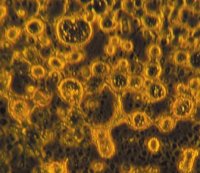

The researchers brought the residue of this icy mixture to room temperature and added liquid water, which would have been present on ancient Earth. They found that the resulting molecules had arranged themselves in spherical vesicles similar in size, shape, and structure to cell membranes.

“At some point, life had to become encapsulated. It had to separate itself from its environment,” says biochemist Jason P. Dworkin of both Ames and SETI. “If this stuff is raining down from space . . . then early life may have had no problem in forming a shell around itself.”

Dworkin, David W. Deamer of UC Santa Cruz, and Scott A. Sandford and Louis J. Allamandola of Ames describe their findings in the Jan. 30 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Deamer reported in 1989 that when organic compounds extracted from the so-called Murchison meteorite interact with water, they form hollow droplets that resemble cell membranes. When he and his colleagues analyzed laboratory ices, “to our surprise and delight, we found that vesicular structures formed that looked very much like those we saw in the Murchison material,” Deamer says.

Also, the vesicles absorb ultraviolet light and convert the energy into visible light. This is akin to the way living cells harvest energy, says Allamandola.

The researchers have “been able to simulate the formation of these vesicles . . . using a pretty simple and completely plausible initial mix of molecules that should be present throughout the interstellar medium,” comments SETI astrobiologist Christopher F. Chyba. “The sort of vesicles that encapsulate life on Earth [could] be everywhere throughout the galaxy.”

Other teams had previously shown that interstellar ices contain compounds that could be precursors for life. Chyba says it’s even more startling to find that such ices are making structures “that really look like a cell membrane.”