Drone photos reveal an early Mesopotamian city made of marsh islands

This urban settlement had neither a city center nor a surrounding defensive wall

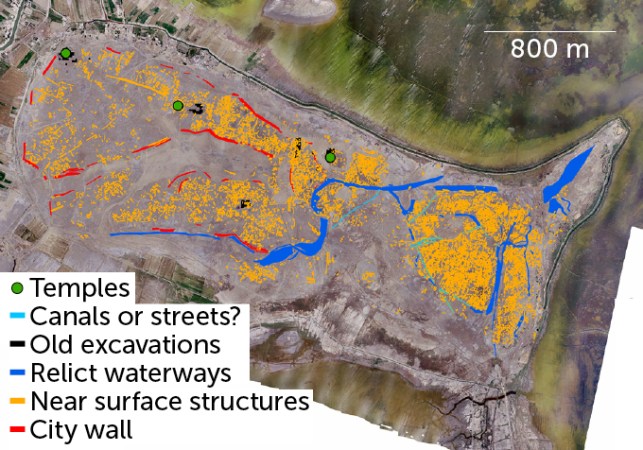

New remote-sensing studies at southern Iraq’s massive Tell al-Hiba site, shown here from the air, support an emerging view that an ancient city there largely consisted of four marsh islands.

Lagash Archaeological Project

A ground-penetrating eye in the sky has helped to rehydrate an ancient southern Mesopotamian city, tagging it as what amounted to a Venice of the Fertile Crescent. Identifying the watery nature of this early metropolis has important implications for how urban life flourished nearly 5,000 years ago between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where modern-day Iraq lies.

Remote-sensing data, mostly gathered by a specially equipped drone, indicate that a vast urban settlement called Lagash largely consisted of four marsh islands connected by waterways, says anthropological archaeologist Emily Hammer of the University of Pennsylvania. These findings add crucial details to an emerging view that southern Mesopotamian cities did not, as traditionally thought, expand outward from temple and administrative districts into irrigated farmlands that were encircled by a single city wall, Hammer reports in the December Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

“There could have been multiple evolving ways for Lagash to be a city of marsh islands as human occupation and environmental change reshaped the landscape,” Hammer says.

Because Lagash had no geographical or ritual center, each city sector developed distinctive economic practices on an individual marsh island, much like the later Italian city of Venice, she suspects. For instance, waterways or canals crisscrossed one marsh island, where fishing and collection of reeds for construction may have predominated.

Two other Lagash marsh islands display evidence of having been bordered by gated walls that enclosed carefully laid out city streets and areas with large kilns, suggesting these sectors were built in stages and may have been the first to be settled. Crop growing and activities such as pottery making may have occurred there.

Drone photographs of what were probably harbors on each marsh island suggest that boat travel connected city sectors. Remains of what may have been footbridges appear in and adjacent to waterways between marsh islands, a possibility that further excavations can explore.

Lagash, which formed the core of one of the world’s earliest states, was founded between about 4,900 and 4,600 years ago. Residents abandoned the site, now known as Tell al-Hiba, around 3,600 years ago, past digs show. It was first excavated more than 40 years ago.

Hidden city

Drone photos taken across a massive site in southern Iraq revealed that buried structures, shown in yellow, from the ancient Mesopotamian city of Lagash clustered in four sectors that had probably been marsh islands. Walls, shown in red, surrounded two large sectors. Now-dry waterways, shown in dark blue, connected sectors and crisscrossed one sector, far right.

Composite map of Lagash based on remote-sensing data

Previous analyses of the timing of ancient wetlands expansions in southern Iraq conducted by anthropological archaeologist Jennifer Pournelle of the University of South Carolina in Columbia indicated that Lagash and other southern Mesopotamian cities were built on raised mounds in marshes. Based on satellite images, archaeologist Elizabeth Stone of Stony Brook University in New York has proposed that Lagash consisted of around 33 marsh islands, many of them quite small.

Drone photos provided a more detailed look at Lagash’s buried structures than possible with satellite images, Hammer says. Guided by initial remote-sensing data gathered from ground level, a drone spent six weeks in 2019 taking high-resolution photographs of much of the site’s surface. Soil moisture and salt absorption from recent heavy rains helped the drone’s technology detect remnants of buildings, walls, streets, waterways and other city features buried near ground level.

Drone data enabled Hammer to narrow down densely inhabited parts of the ancient city to three islands, she says. A possibility exists that those islands were part of delta channels extending toward the Persian Gulf. A smaller, fourth island was dominated by a large temple.

Hammer’s drone probe of Lagash “confirms the idea of settled islands interconnected by watercourses,” says University of Chicago archaeologist Augusta McMahon, one of three co–field directors of ongoing excavations at the site.

Drone evidence of contrasting neighborhoods on different marsh islands, some looking planned and others more haphazardly arranged, reflect waves of immigration into Lagash between around 4,600 and 4,350 years ago, McMahon suggests. Excavated material indicates that new arrivals included residents of nearby and distant villages, mobile herders looking to settle down and slave laborers captured from neighboring city-states.

Dense clusters of residences and other buildings across much of Lagash suggest that tens of thousands of people lived there during its heyday, Hammer says. At that time, the city covered an estimated 4 to 6 square kilometers, nearly the area of Chicago.

It’s unclear whether northern Mesopotamian cities from around 6,000 years ago, which were not located in marshes, contained separate city sectors (SN: 2/5/08). But Lagash and other southern Mesopotamian cities likely exploited water transport and trade among closely spaced settlements, enabling unprecedented growth, says archaeologist Guillermo Algaze of the University of California, San Diego.

Lagash stands out as an early southern Mesopotamian city frozen in time, Hammer says. Nearby cities continued to be inhabited for a thousand years or more after Lagash’s abandonment, when the region had become less watery and sectors of longer-lasting cities had expanded and merged. At Lagash, “we have a rare opportunity to see what other ancient cities in the region looked like earlier in time,” Hammer says.