In the early morning hours of Nov. 18, sky watchers in North America may be treated to one of the most spectacular displays of shooting stars they’re likely to see for a generation, if not longer.

The event, called the Leonid meteor shower, is an annual happening, but this year’s display will stand out. North American observers will see “a greatly enhanced shower,” says William Cooke of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.

At its predicted peak over the continental United States, between 4 a.m. and 6 a.m. EST, observers may see as many as 800 meteors streaking across the sky in a single hour. With the moon out of sight, spectators will have optimal viewing conditions if skies are clear and their location free from light pollution.

The Leonid shower, so named because it seems to emanate from the constellation Leo, occurs every November. That’s when Earth plows through dust grains, or meteoroids, expelled by Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle during centuries of passages near the sun. When Earth’s atmosphere slams into the meteoroids, they burn up, generating the streaks of light called meteors.

About every 33 years, when the comet passes closest to the sun, Earth encounters a larger than normal amount of debris. This results in an unusually intense shower or even a storm. The last major storm appeared in 1966.

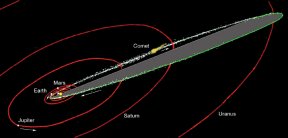

Astronomers recently realized that the dust shed by Tempel-Tuttle each time it nears the sun forms a separate new stream of debris (SN: 12/4/99, p. 357: http://www.sciencenews.org/sn_arc99/12_4_99/fob3.htm). Although the streams stretch along the comet’s orbit, they remain narrow.

A full-blown meteor storm occurs when Earth goes directly through the center of one of the streams, says Mark Bailey of Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland. “It’s a little like ten-pin bowling; sometimes you strike lucky, sometimes you miss them all,” he says.

This year, several teams predict, Earth will rack up three strikes. They calculate that the planet will successively plunge through debris streams shed by Tempel-Tuttle in 1767, 1699, and 1866. According to Cooke’s team, Earth will also intercept streams from 1633, 1666, and 1799. “In our model, the biggest contribution comes from the 1799 stream,” which would make Hawaii the best viewing spot in North America, notes Cooke.

In contrast, Rob McNaught of the Australian National University in Weston and David J. Asher of Armagh Observatory calculate that the most intense fireworks will appear over East Asia and Australia. They agree, however, that North America’s display, although more modest, will be one of the best for years to come.

While dazzling to people, the shower might actually daze satellites, including the Hubble Space Telescope. If a meteoroid slams into a spacecraft, the clouds of charged gas that the collision creates could short-circuit or destroy electronic equipment. That’s why satellites will be commanded to point away from Leo.

Don’t bother looking for a light show on Nov. 18 before midnight local time, when Leo rises. The meteors will appear to originate from Leo’s sickle, which resembles a backwards question mark and lies near the bright star Regulus. It’s best to view the whole sky surrounding Leo’s sickle, notes Brian G. Marsden of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. Lie down in a comfortable deck chair away from buildings and trees and just use your naked eye, he advises.

If clouds put a damper on next week’s Leonid display, North Americans may next year have one last chance to see a really big show, Asher says. He and McNaught calculate that at its peak, the Leonid shower in 2002 will be more than 10 times as intense over the United States as in 2001. However, a nearly full moon next year will dramatically reduce the number of meteors visible.

Cooke maintains that this year’s shower, not the one in 2002, will be the showstopper.