A species of Tanzanian monkey first identified last year may actually require a separate genus, says an international research team. It would be the first new genus for monkeys in 79 years.

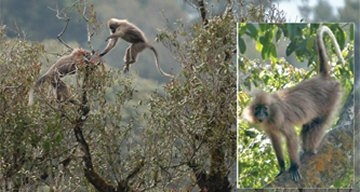

Last year, the rare, reclusive monkey was classified as a mangabey and named Lophocebus kipunji (SN: 5/21/05, p. 324: New Mammals: Coincidence, shopping yield two species). The two research groups that named it had worked from field observations and photographs but didn’t have a specimen for anatomical and genetic analysis.

Since then, Tim R.B. Davenport of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s branch in Tanzania, one of the original namers, received a kipunji cadaver from a farmer’s trap. Its body characteristics and DNA place the species in a new genus, located on the family tree close to baboons, Davenport and his collaborators report in the June 2 Science.

“This will, of course, generate some controversy,” says Davenport’s collaborator Link Olson of the University of Alaska Museum in Fairbanks, who analyzed the DNA.

Taxonomists have often split and revised genera, but the last new monkey genus was named in 1927: Oreonax, a type of woolly monkey.

Last year, Davenport’s team and a group including Trevor Jones of Udzungwa Mountain National Park happened upon kipunjis in separate forests. They heard about each other’s work only when a member of each team happened to meet in a bar.

Last August, a farmer near Mount Rungwe found a dead kipunji in a trap he set for animals raiding his maize field. Davenport sought advice on specimen handling from mammalogist William T. Stanley of Chicago’s Field Museum.

Stanley was doing fieldwork near an island village when his cell phone received scraps of text messages from Davenport. “I was running around this soccer field on the edge of the Indian Ocean trying to get a signal,” he says.

Stanley flew to Tanzania and with the biologists there distributed specimen samples to labs in Tanzania and the United States.

Olson reported that the five sections of kipunji DNA that he analyzed put the animal closer to baboons than to mangabeys. But when researchers compared the young male with baboons in the Field Museum’s collection, they concluded that it didn’t fit well among baboons, says Stanley.

Because the animal’s genetics argues against mangabeys and the monkey doesn’t look like a baboon, the researchers proposed the new genus: Rungwecebus.

Todd Disotell of New York University (NYU) finds the proposal “extraordinarily premature.” For example, he says that the database sequences Olson used need updating.

NYU primatologist Clifford Jolly, who has studied baboon evolution, is likewise skeptical. However, he says that if the new family tree turns out to be right, kipunjis could be interesting survivors of an ancient lineage.