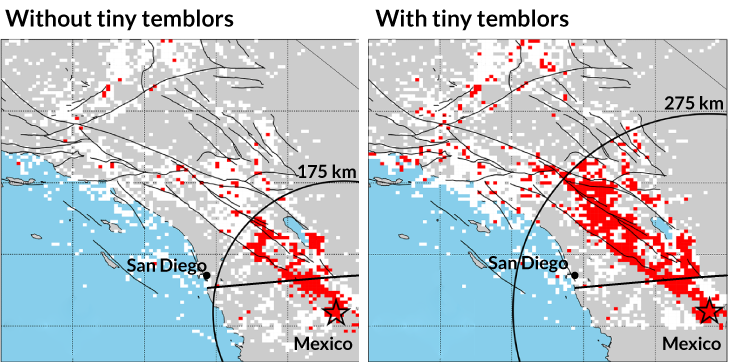

COUNTING QUAKES The magnitude 7.2 El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake triggered numerous aftershocks across much of Southern California when it struck Baja California, Mexico, in 2010. A new study has identified more than a million tiny quakes recorded by seismometers in the region from 2008 to 2017, including hundreds of previously unnoticed aftershocks from the 2010 quake.

Centro de Investigacion Cientifica y de Educacion Superior de Ensenada (CICESE)

In between the “big ones,” millions of tiny, undetected earthquakes rumble through the ground. Now, a new study uncovers a decade’s worth of such “hidden” quakes in Southern California, increasing the number of quakes logged in the region tenfold. Such troves of quake data could shake up what’s known about how temblors are born belowground, and how they can interact and trigger one another, researchers report online April 18 in Science.

The researchers used a technique called template matching to mine an existing archive of earthquakes, recorded by seismometers and other instruments in the region from 2008 to 2017. The team was searching for quakes of such small magnitude that their signals were previously too small to be separated from noise. The results boosted the number of earthquakes in the Southern California Seismic Network archive to 1.8 million.

Statistical analyses using this wealth of new data could help researchers suss out information about seismic activity that wouldn’t have been possible previously. “You can’t do statistics with small numbers,” says Emily Brodsky, a seismologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who wasn’t involved in the new study.

She likens the usefulness of tiny quakes to that of fruit flies: They’re like small but abundant laboratory model organisms. With large populations — whether of fruit flies or earthquakes — you can learn what’s robust and what’s a fluke; separating the two is a chronic problem in earthquake studies, Brodsky says.

Triggered swarm

A broader swath of Earth rumbled with aftershocks triggered by the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah quake in Baja California, just south of the U.S.-Mexico border, than had been thought. The original earthquake archive (left) showed aftershocks as far as 175 kilometers from the epicenter. A new analysis (right) reveals tiny quakes as far as 275 kilometers away triggered by the main shock, increasing the number of recorded aftershocks by 142 percent (red dots indicate above-average seismicity). That suggests that changes in stress on nearby faults aren’t the only ways that earthquakes interact. Other subtle shifts, such as changes in fluid pressure near the edges of the fault zone, could be responsible for how one quake can trigger another.

Researchers have long suspected the tiny temblors existed. In 1944, scientists observed a peculiar relationship between earthquake magnitudes and frequencies: For every unit increase in magnitude, there are 10 times fewer quakes. That means that the vast majority of quakes are small. In fact, it’s difficult to distinguish many of them from other sources of shaking recorded by seismometers.

“These instruments are incredibly sensitive,” says study coauthor Zachary Ross, a seismologist at Caltech. “They record construction vibrations, vehicles, trains, air traffic, ocean noises from waves.” These sources of noise produce waves with similar amplitudes to those of quakes with magnitudes just above zero, he says.

Template matching, first proposed 15 years ago, separates the quake signals from all that noise. Scientists first take existing data for a larger quake that occurred in a fault zone. The series of wiggles recorded by a seismometer due to a given quake on a given fault follows a pattern as distinct as a fingerprint, because the waves are modified in a particular way by the rocks they pass through underground. Another quake occurring on the same fault will follow the same pattern — even if it’s much, much smaller.

“We look for something that has a near identical waveform,” Ross says. Previous studies have used this technique in a limited way, mapping out tiny aftershocks from a large quake, for instance. But the new study is the first to take on a whole regional seismic database.

The computationally intensive project took three years. But the rewards are worth it, Ross says. For example, the new catalog fills in gaps between larger quakes that reveal how those seemingly unrelated events might not be so unrelated after all.

“We’re starting to complete the story about the interactions between these events,” Ross says. That includes not only observing how earthquakes might cluster in space and time, but also observing the tiny foreshocks that might precede a larger quake. From that, he says, scientists may be able to infer something about the physics of earthquake nucleation — how a particular temblor was born.

Brodsky also notes that uncovering all this hidden data could have a big impact when it comes to linking human activities to earthquakes, such as the magnitude 5.5 quake that struck Pohang, South Korea, in 2017 (SN: 5/26/18, p. 8). In March, a government-commissioned panel determined that the quake was triggered by a geothermal plant injecting water underground.

“Arguments for whether or not something is human-induced revolve around timing and location,” she says. “The thing is, very often there’s a delay, so that timing becomes ambiguous.” Being able to see whether an apparent delay between human activities and a big temblor is actually filled with tiny quakes — possibly revealing a continuous process — could be a game changer.