About 20 kilometers southwest of New Orleans, one of the U.S. Geological Survey’s benchmarks sits atop a concrete column that pokes above the waves about 5 meters from the shore of Couba Island. The small brass disk, one of thousands that the agency has installed throughout the country, serves as a reference point for surveyors and mapmakers. Why did agency personnel place what should be a readily accessible guidepost in the thigh-deep waters of a Louisiana bayou? The answer’s easy: They didn’t. When the disk was installed in 1932, it sat high and dry in someone’s backyard.

Several factors have contributed to making the benchmark’s locale wet. In recent years, the sea level has risen slowly but surely. Just as gradually, the land that the benchmark sits upon has subsided—in part because of the extraction of oil and natural gas from strata beneath the bayou. But another important cause of the ground sinking is the waning of sediment deposition by the Mississippi River. Between the land slowly sinking and the water rising, Louisiana each hour is losing ground equal to two football fields.

The dearth of sediment now reaching river deltas isn’t a trend unique to the Mississippi. It occurs even though human activities such as agriculture and deforestation are eroding land faster than ever before, boosting the amount of silt and other material carried by rivers through their inland reaches. The problem is that much of that suspended sediment never reaches the sea because it gets trapped by thousands of dams—a situation that will only get worse if the construction of dozens of large dams in developing nations around the world goes ahead as planned.

Going down?

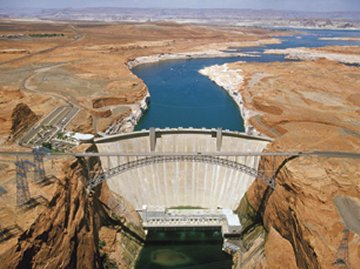

Dams serve many useful functions, including flood control, the generation of hydroelectric power, and the impoundment of water for irrigation, drinking, and recreation. Worldwide, there are more than 45,000 dams that are at least 15 m tall, says Catherine A. Reidy, a hydrologist at Umeå University in Sweden. Together, these large dams are capable of holding back about 6,500 cubic kilometers of water, about 15 percent of the water volume carried by the world’s rivers each year.

Reidy and her colleagues recently tallied the dams on the world’s large river systems—systems that, if undammed, would have an average flow rate of 350 cubic meters per second in at least one place along the river or its tributaries. The 292 rivers meeting that criterion drain more than 54 percent of the world’s land surface and carry 60 percent of the world’s river flow. The researchers couldn’t find reliable data, and so didn’t consider, rivers in much of Indonesia and part of Malaysia, says Reidy.

Flow in 172 large river systems—more than half of the systems that the researchers studied—is substantially affected by dams, Reidy and her colleagues report in the April 15 Science.

When dams reduce suspended sediment at a river’s mouth and beyond, some benefits can accrue. Harbors may not need to be dredged as often, and in the less murky waters, offshore coral reefs may receive more sunlight.

On the downside, however, the reduction of sediment flow, however, contributes to subsidence and loss of land in many river deltas, says James P.M. Syvitski of the University of Colorado at Boulder. Along Spain’s Ebro River delta, for example, engineers have trucked in more than 110 million tons of sediment since 1983 to replenish beaches. The Ebro and its tributaries have 187 dams that trap about 99 percent of the sediment that would otherwise reach the delta.

Likewise, dams along the Nile interrupt the seaward trek of about 98 percent of the river’s suspended material. At the mouth of the Nile, the coastline is retreating by about 10 m each year, Syvitski says.

Drops in sediment flow exacerbate a variety of problems beyond loss of coastal lands. For example, carbon-rich material in sediment nourishes organisms at the base of the food chain in estuaries and near-shore waters. When those small animals become scarce, larger creatures that dine on them go hungry. The sardine catch at the mouth of the Nile plummeted 95 percent after the Aswan Dam, completed in 1970, began intercepting nutrient-rich sediment destined for the Mediterranean, says Syvitski.

Similarly, the shrimp catch in Mexico’s Gulf of California dropped significantly when dams along stretches of the Colorado River in the United States began operation in the mid-20th century.

In some locales, accumulating sediments serve yet another purpose: They bury pollutants that people have generated near the shore. The faster silt and other material collect on the seafloor, the more quickly toxic materials can be isolated from the food chain, says Syvitski.

Down the river

Scientists have monitored the flow of silt and other material to the sea in less than 10 percent of the world’s rivers. Most of those measurements have now ceased—many of them victims of budget cuts a decade or more ago, says Syvitski. To estimate human impact on sediment flow, he and his colleagues developed several analytical tools.

One of their models, based on topographic data, divides all of Earth’s landmasses into a grid of 60,000-or-so cells that each measures 0.5° latitude by 0.5° longitude. The data define almost 6,300 drainage basins with areas greater than 100 square kilometers, says Syvitski. Nearly 4,500 of these river basins are active, providing fresh water and sediment flow to the coastal regions. The others, in frozen regions, make little contribution.

Another model by Syvitski’s team estimates the total volume of fresh water carried by all the world’s rivers. It uses flow-volume data gathered by 663 gauges. The rivers monitored by these gauges drain about 72 percent of the area included in active drainage basins. The simulation has been further adjusted to account for evaporative losses caused by irrigation and for modern-day transfers of water, when people pump it from one river basin that gets sufficient precipitation to another basin that doesn’t.

To estimate the volume of sediment flowing to the sea, Syvitski and his colleagues created a model that takes into account a river basin’s area, topography, and climate. That model has been calibrated with sediment data from 340 rivers, most of which are pristine or were observed before human activity significantly influenced their sediment content.

Analyses combining these models suggest that, in the prehuman era, the world’s rivers carried about 15.5 billion metric tons of silt, sand, and other material to the sea each year. Of that tonnage, about 40 percent spilled off the continent of Asia. Even though South American rivers together carried more water each year than Asian rivers did, they dumped into the ocean less than half the volume of sediment that their Asian counterparts did. Differences in the topography of the two continents account for much of that disparity, says Syvitski. For example, Asia is larger and has a higher proportion of its land at high altitude than South America does.

More than 60 percent of the sediment delivered to the world’s oceans in the prehuman world originated from erosion in mountainous areas with elevations greater than 3 km above sea level. The steepness of the terrain in such regions makes flowing water a more powerful scouring agent.

Also, two-thirds of the sediment was dumped into the ocean by rivers flowing through warm, temperate regions, the portions of the world where flow volumes are the greatest. Syvitski and his colleagues present their findings in the April 15 Science.

Scour power

Accurate measurements of sediment volumes transported by rivers extend back only a century or two at best. However, by measuring the volume of marine sediments that were laid down near continents in various eras, scientists can estimate the flow rates of material carried by ancient waterways.

Rates of offshore sediment accumulation have varied significantly over geologic time, says Bruce H. Wilkinson of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His analyses of marine sediment suggest that natural erosion, on average, strips away the equivalent of a 24.4-m-thick layer of material from continental landmasses every 1 million years.

Wilkinson’s models indicate that the bulk of that sediment comes from steep, mountainous regions. His results attribute an even higher proportion of the loss to highlands than Syvitski’s data do. Wilkinson estimates that about 86 percent of natural erosion occurs at elevations greater than 4 km above sea level, a region that represents only 2 percent of Earth’s surface.

Human activities are contributing to sediment erosion at an ever-increasing pace, says Wilkinson. Unlike natural erosion, most of the anthropogenic loss occurs at low elevations, where people live, build, and farm. Agriculture takes up about 40 percent of Earth’s surface, and most of that acreage lies less than 2 km above sea level, he notes.

Historical trends in population and land use suggest that human-triggered erosion overtook natural processes to become the prime earthmover between 1,000 and 1,500 years ago. Scientists estimate that people today mobilize about 15 times as much sediment as natural processes do. Modern agricultural techniques strip soil from cropland at a rate that would remove a 650-m-thick surface layer every million years.

At today’s rates, erosion triggered by human activity around the globe would scour away enough material to fill the Grand Canyon in just 50 years, says Wilkinson.

Scientists have accurate comparisons of natural sediment flow on 217 rivers before and after dams were constructed, says Syvitski. Those data indicate that large reservoirs behind dams now intercept about 20 percent of the sediment that’s headed for the sea on those rivers and that small reservoirs trap about 6 percent.

Therefore, the annual worldwide total of sediment reaching the ocean on all rivers, dammed and undammed, is about 12.6 billion tons, a decrease of about 10 percent from the amount that spilled into the sea in the prehuman era. With modern rates of erosion and no dams to trap sediment, about 17.8 billion tons of material would reach the coast each year, Syvitski says.

Other analyses suggest that inland reservoirs today hold about 100 billion metric tons of sediment. Most of that material, with a carbon content of 1 to 3 percent, is sequestered behind dams that have been constructed in the past 50 years, says Syvitski. That carbon-rich matter, now locked away, is unavailable to nourish coastal ecosystems.

The future be dammed

For decades, for better or worse, people have been on a dam-building binge that would be the envy of any beaver. “We’ve built one large dam every day for the past 100 years,” Syvitski notes.

And the urge to continue building dams is strong: Economic activity in large river systems with dams is on average about 25 times higher than it is on an undammed river, says Reidy. At least 273 large dams are either planned or now under construction on 46 large river systems, and more than 20 of those are planned for systems previously unaffected by dams.

As future dams reach completion, their reservoirs will begin to fill, and the silt, sand, and other material carried by those waterways will end its traditional march to the sea. Downstream, more river deltas will become starved for fresh sediment, and regions that once received enough muck to stay above water will slowly begin to subside. Rising sea levels will aggravate the problem.

In that not-so-far-off future, residents of many more regions will come to know the sinking feeling that people in Louisiana’s bayou country have had for decades.