NASA’s Perseverance rover snagged its first Martian rock samples

The rock bits are the first from Mars slated to eventually return to Earth

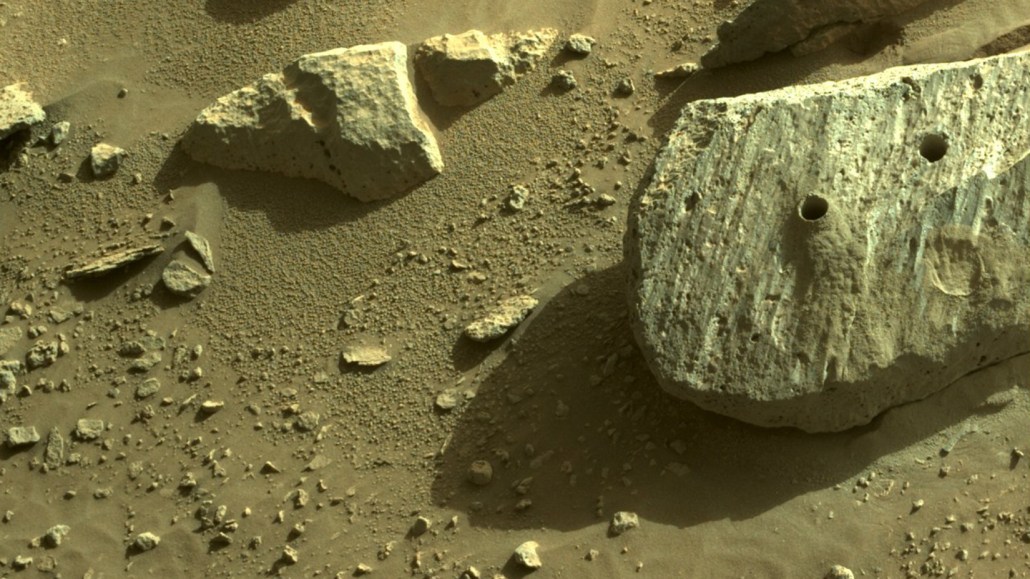

The Perseverance rover drilled two cylinders of stone out of a Martian rock called Rochette in early September. The samples may eventually return to Earth for further study.

JPL-Caltech/NASA

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

The Perseverance rover has captured its first two slices of Mars.

NASA’s latest Mars rover drilled into a flat rock nicknamed Rochette on September 1 and filled a roughly finger-sized tube with stone. The sample is the first ever destined to be sent back to Earth for further study. On September 7, the rover snagged a second sample from the same rock. Both are now stored in airtight tubes inside the rover’s body.

Getting pairs of samples from every rock it drills is “a little bit of an insurance policy,” says deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, Calif. It means the rover can drop identical stores of samples in two different places, boosting chances that a future mission will be able to pick up at least one set.

The successful drilling is a comeback story for Perseverance. The rover’s first attempt to take a bit of Mars ended with the sample crumbling to dust, leaving an empty tube (SN: 8/19/21). Scientists think that rock was too soft to hold up to the drill.

Nevertheless, the rover persevered.

“Even though some of its rocks are not, Mars is hard,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, in a September 10 news briefing.

Rochette is a hard rock that appears to have been less severely eroded by millennia of Martian weather (SN: 7/14/20). (Fun fact: All the rocks Perseverance drills into will get names related to national parks; the region on Mars the rover is now exploring is called Mercantour, so the name Rochette — or “Little Rock” — comes from a village in France near Mercantour National Park.)

Rover measurements of the rock’s texture and chemistry suggests that it’s made of basalt and may have been part of an ancient lava flow. That’s useful because volcanic rocks preserve their ages well, Stack Morgan says. When scientists on Earth get their hands on the sample, they’ll be able to use the concentrations of certain elements and isotopes to figure out exactly how old the rock is — something that’s never been done for a pristine Martian rock.

Rochette also contains salt minerals that probably formed when the rock interacted with water over long time periods. That could suggest groundwater moving through the Martian subsurface, maybe creating habitable environments within the rocks, Stack Morgan says.

“It really feels like this rich treasure trove of information for when we get this sample back,” Stack Morgan says.

Once a future mission brings the rocks back to Earth, scientists can search inside those salts for tiny fluid bubbles that might be trapped there. “That would give us a glimpse of Jezero crater at the time when it was wet and was able to sustain ancient Martian life,” said planetary scientist Yulia Goreva of JPL at the news briefing.

Scientists will have to be patient, though — the earliest any samples will make it back to Earth is 2031. But it’s still a historic milestone, says planetary scientist Meenakshi Wadhwa of Arizona State University in Tempe.

“These represent the beginning of Mars sample return,” said Wadhwa said at the news briefing. “I’ve dreamed of having samples back from Mars to analyze in my lab since I was a graduate student. We’ve talked about Mars sample return for decades. Now it’s starting to actually feel real.”