From the November 17, 1934, issue

EXPLORE MYSTERY ISLE

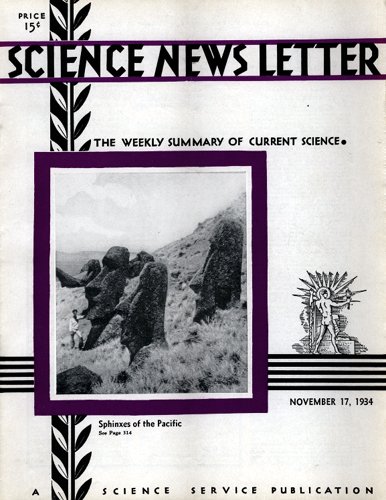

Easter Island, loneliest inhabited isle in the Pacific, will be invaded by two scientific expeditions this year.

A party of French-Belgian-Swiss scientists has already landed. Americans will arrive later. The men of science will climb grassy hillsides of the island to peer at hundreds of great stone faces that have so far out-sphinxed the sphinx in determined silence about the past.

In some long-ago era of hustling energy, Easter Islanders turned out statuary by the ton. Using volcanic craters on the island as quarries, the people carved out heads and torsos—little fellows 3 feet high; big fellows 20, 30 feet; even one giant 70 feet tall. Both men and women were portrayed.

They had a pattern for their art, and they stuck to it. The stone faces had to have long noses, disdainful mouths, jutting eyebrows.

In another quarry, workers ran a stone-hat factory, hewing out a red-tinted stone for top hats to adorn the heads of the gray stone giants. A red hat for a 30-foot giant would weigh fully 3 tons.

When an image was finished, the workers slid it down the hillside, and then somehow pulled or pushed the statues—some weighed as much as 40 tons—to an appropriate site. All the faces were made to turn inland, toward the graves of Easter Island’s dead.

AIR A HUNDRED MILES UP MAY BE WARM AS A SUMMER DAY

Further proof that the layers of ionized atmosphere of the Earth from 62 to 124 miles above sea level have a fairly constant temperature, regardless of the time of day, night, or season, is presented in a report (Physical Review, Nov. 1) prepared by Dr. E.O. Hulburt of the Naval Research Laboratory.

Moreover, new data taken by many investigators scattered all over the world indicate that the temperature of the high-altitude layer may be as great as that of an average summer’s day at the Earth’s surface, about 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

ASTRONOMER EXPLAINS STAR GOING TWO WAYS AT ONCE

The mystery of stars that go two ways at once, the outer part expanding and the inner part contracting, is cleared up by the South African astronomer A.E.H. Bleksley of the University of Witwatersrand (Nature, Oct. 27).

The two-way stars are the pulsating stars known as the “Cepheid variables.” They are relatively common. Their paradoxical action of expanding and contracting at the same time in different places was explained by Mr. Bleksley as the result of his calculations on the temperatures and luminosities of several of the stars, particularly the one known technically as RS Boötis.

It was assumed by scientists that such stars ought to be the hottest and brightest when they reached the greatest contraction. Astrophysicists were therefore puzzled to find that when the star was getting brighter and brighter, its outer atmosphere was moving toward them, or away from the center.

The finding of this kind of star action threw doubts on the whole “pulsation” theory of the Cepheid variable type of star.