More water moved into and out of the atmosphere in 2000 than in 1950, making saltier parts of the world’s oceans saltier and fresher waters less salty, researchers report in the April 27 Science.

A warming planet may be to blame. Simulations in the new study suggest evaporation and rainfall got a 4 percent boost as surface temperatures rose half a degree Celsius. That boost is a bigger change than previous studies had suggested, but fits with the idea that a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

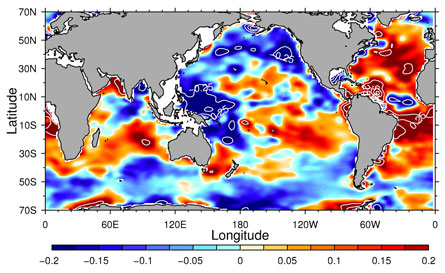

“We see big broad patterns of change,” says Paul Durack, an oceanographer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. “Regions dominated by evaporation became saltier, while regions dominated by rainfall became fresher.”

Measuring such global changes in Earth’s evaporation and rain cycle has never been easy. Rain gauges on land or at sea tend to be sparsely distributed, and the exact positions of such instruments decades ago isn’t always known.

“Comparing different times gets difficult because you typically have more and better data for the later times,” says William Ingram, an atmospheric physicist at the Met Office Hadley Centre in Exeter and the University of Oxford in England.

Ocean salinity provides a fairly stable, reliable way to measure how much water goes up and comes down, says Ingram. Small fluctuations in evaporation and rainfall tend to get smoothed out over time, helping scientists to tease out long-term trends.

Durack’s team analyzed 1.7 million salinity measurements made by ships during the second half of the 20th century. Other researchers had already seen patterns of change in these data, but Durack and his colleagues sharpened the picture. A network of autonomous buoys deployed in the 21st century helped to fill in gaps in the record, particularly in high latitudes where winter storms keep ships away.

“This is excellent work, reaching deep … to quantify an elusive ocean variable,” says Tim Boyer, a physical oceanographer at the National Oceanographic Data Center in Silver Spring, Md.

As rising greenhouse gas levels continue to warm Earth, the water cycle will churn even harder. Every extra degree is estimated to increase the amount of water moving around by 8 percent.

And what happens in the oceans doesn’t stay in the oceans. The cycle that occurs over water extends over land as well. Dry lands across the globe — Australia, for instance — will probably get drier in the future, as wet places get even wetter, says Durack.