Rats keep getting into paradise. And when they discover a taste for escargot, it’s an infernal problem for native populations.

At a study site high in the mountains on the Hawaiian island of Molokai, tree snails of the species Partulina redfieldi thrived for 12 years and then declined catastrophically, says zoologist Michael G. Hadfield of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The culprits were introduced rats that started scouring trees for snails, Hadfield and Jennifer Saufler, now at University College London, report in the August Biological Invasions.

Rats have hitchhiked along as people settled the globe and have changed their new homes by feasting on native species such as snails and ground-nesting birds. The Molokai study provides an unusual look at rat damage because the team collected data before and after a burst of attacks, Hadfield says.

The Hawaiian islands once had extraordinary snails, about 750 species found nowhere else, Hadfield notes. All together the islands once hosted more snail species than did the other 49 states and Canada combined. Darwin contemplated Hawaiian snail variation, and the showy species in the Achatinellinae subfamily, which live in trees, have become a classic example of the wide diversity of species that can develop on islands.

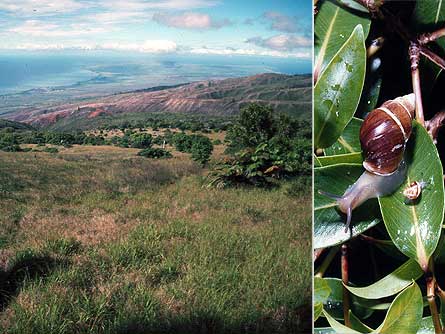

But more than 70 percent or so of those 750 species have gone extinct, including some of the storied tree snails, Hadfield says. As part of a broad research program on snail biology and conservation, he and his colleagues started in 1983 to monitor P. redfieldi snails in ohia trees dotting a mountain meadow.

These snails spend their entire lives, which can last 18 years or more, in one tree, the researchers found. And biology doesn’t make for fast comebacks. P. redfieldi has to reach 3 to 5 years of age before reproducing, and even then the snails have, through live birth, only about five babies a year.

Despite this leisurely reproductive biology, snail numbers in four meadow trees at least doubled during the first dozen years of the study. From 1995 through 1996, though, the snail numbers plunged more than 80 percent, the researchers report. At the same time, the number of rat-chewed shells found under the trees jumped. Hadfield says he thinks the number of rats boomed, and then some of them “discovered that the trees were full of dinner.”

“Rats are copycats,” he says. Other research has shown that a few rats discovering a banquet can inspire others to visit and feed repeatedly.

After Hadfield first saw the devastation, The Nature Conservancy started setting out poisoned bait to reduce the rat numbers. But Hadfield’s team reports that the snail population stayed small through 2006.

“There has been a fairly long-standing interest in the role of rats in Pacific island ecosystems,” says archaeologist Stephen Athens of the International Archaeological Research Institute, an independent research organization in Honolulu. “What seems to have changed is a new appreciation of how truly devastating rats can be.”

Athens says the study doesn’t have hundreds of years of data to address the big question of what rats have done to Hawaiian ecosystems untouched by humans, but it should help resource managers try to save what’s left of the snail species.

Predators loom large in the uncertain future of Hawaii’s once-glorious snails, Hadfield says. Native snails are falling prey to three rat species that now prowl the islands and to an introduced flatworm and a predatory snail. These menaces haven’t completely killed any hope Hadfield has for preserving the remnants of Hawaii’s snails. Yet, he says his new analysis suggests snail preservationists are going to have to get tough.