With one island’s losses, the king penguin species shrinks by a third

It’s unclear what has happened to what was the largest of king penguin colonies in the 1980s

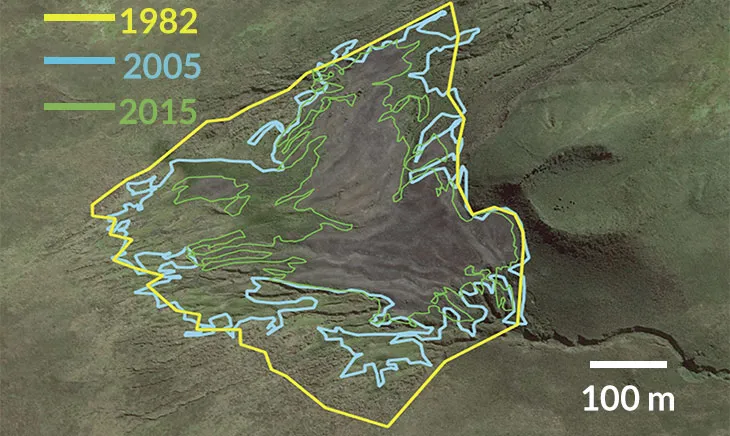

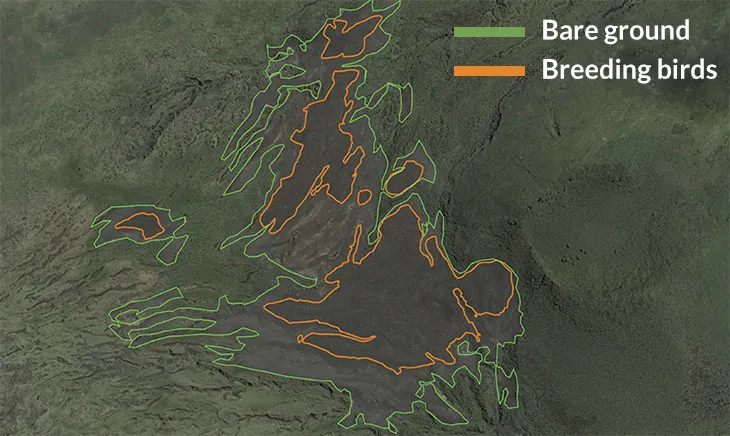

WHEN KINGS RULED The largest colony of king penguins (shown in 1982) once had some 500,000 pairs of breeding birds a season, but recently discovered losses are so big they could affect the species’ total population.

J.C. Stahl