Parents’ obesity may affect children’s brains; beetle with bifocals

More news from the Society for Neuroscience meeting

Beetle bifocals

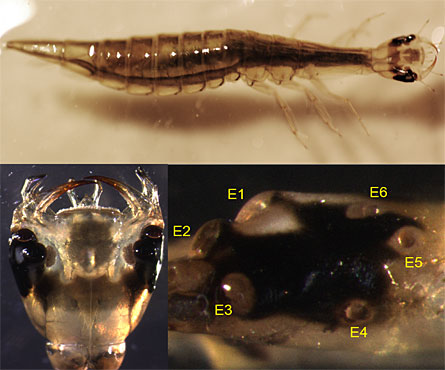

CHICAGO — Sunburst diving beetle (Thermonectus marmoratus) larvae possess a grand total of 12 eyes, four of which are naturally bifocal, researchers reported October 17 at the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting. These marine beetle larvae are voracious predators, tracking and eating mosquito larvae. The 12 eyes span the head, giving the beetle larvae a panoramic view of the world. Annette Stowasser and her colleagues at the University of Cincinnati found that the four most prominent eyes on these aquatic hunters hold several retinas apiece, allowing the eyes to clearly focus on objects at two distinct distances. Stowasser and her colleagues speculate that the strange eyes might help beetle larvae better spy prey. The researchers are particularly interested in understanding how and why the beetle larvae’s unusual visual system evolved. —Laura Sanders

Obesity’s long reach on the brain

Research in mice looks at effects of diet and weight on offspring

CHICAGO — Sons of obese mother mice grow up fat, anxious and with signs of brain inflammation, Staci D. Bilbo of Duke University in Durham, N.C., and colleagues reported October 18 at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience.

Scientists have known for some time that obesity is associated with low-grade inflammation in the body, but no one had really checked whether being obese could inflame the brain. And the consequences of an inflamed brain for learning and memory are also unknown.

Researchers compared the offspring of female mice that ate a low-fat diet or one of two kinds of high-fat diets — saturated fats or a mix of saturated and trans fats. Scientists found that the brains of pups born to moms fed a diet high in saturated fats showed increased levels of interleukin-1, a marker of inflammation. The pups of moms on the high trans-fat diet didn’t have increased IL-1 in their brains, but their livers did show signs of inflammation, as expected from previous work linking trans fats to inflammation and disease.

“It appears that trans fats are bad for the liver, but saturated fats are much worse for the brain,” Bilbo said.

What the researchers really wanted to know is whether the fat-induced inflammation hurt the mice’s brains and impaired their ability to learn and remember. Previous research has shown that high levels of IL-1 impair learning and memory. But, to Bilbo’s surprise, fat male mice from the saturated fat group didn’t have obvious learning and memory problems when tested in a water maze.

There are several explanations for the finding, Bilbo says. For one thing, these male offspring are more anxious and so swim faster than their sisters and offspring from the other groups. Sons of mother mice fed the high-saturated-fat diet are also bigger, which makes them more likely to bump into the submerged platform. The other possibility, she says, is that a little bit of inflammation actually gives this group an initial edge. Just as too much IL-1 is bad for the brain, too little isn’t good either. As with many biological molecules, a plot of the optimal levels of IL-1 looks like an inverted U, with some intermediate level of the protein correlating with better learning and memory. The learning advantage might disappear when levels of IL-1 shoot up during an infection, a possibility the researchers are testing.

Bilbo’s findings fit with earlier data linking a mother’s diet to the health and behavior of offspring, says Quentin Pittman of the University of Calgary in Canada. The new study showing that high-fat diets increase inflammation in the brain also raises the specter of future problems. “Inflammation within the hippocampus is associated with increased risk for outcomes like Alzheimer’s disease, so it suggests a very scary possibility that some of us are programmed for Alzheimer’s susceptibility from the time we are born,” he says.

The affected male mice’s obesity persisted into adulthood even though they were switched to low-fat diets when weaned. Bilbo is analyzing data to find out how many generations might pay the price for mom’s over-indulgence. —Tina Hesman Saey