A very specific kind of brain cell dies off in people with Parkinson’s

Dopamine-making nerve cells may not be equally culpable in the disease after all

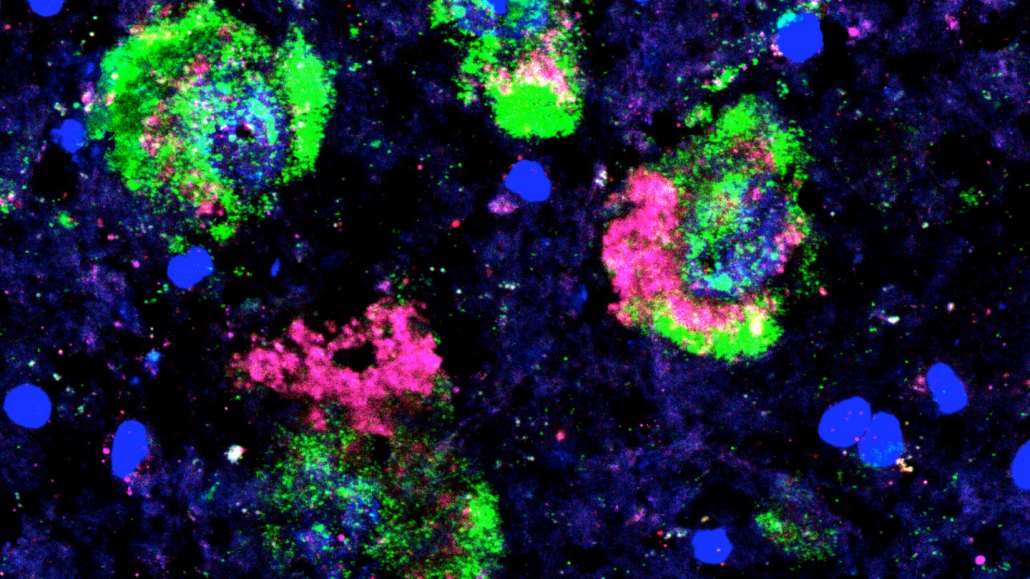

Certain human brain cells selectively die off in Parkinson’s disease. Among cells that produce the chemical messenger dopamine (green), an active AGTR1 gene (labeled in magenta) sets these vulnerable cells apart.

Macosko Lab

Deep in the human brain, a very specific kind of cell dies during Parkinson’s disease.

For the first time, researchers have sorted large numbers of human brain cells in the substantia nigra into 10 distinct types. Just one is especially vulnerable in Parkinson’s disease, the team reports May 5 in Nature Neuroscience. The result could lead to a clearer view of how Parkinson’s takes hold, and perhaps even ways to stop it.

The new research “goes right to the core of the matter,” says neuroscientist Raj Awatramani of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Pinpointing the brain cells that seem to be especially susceptible to the devastating disease is “the strength of this paper,” says Awatramani, who was not involved in the study.

Parkinson’s disease steals people’s ability to move smoothly, leaving balance problems, tremors and rigidity. In the United States, nearly 1 million people are estimated to have Parkinson’s. Scientists have known for decades that these symptoms come with the death of nerve cells in the substantia nigra. Neurons there churn out dopamine, a chemical signal involved in movement, among other jobs (SN: 9/7/17).

But those dopamine-making neurons are not all equally vulnerable in Parkinson’s, it turns out.

“This seemed like an opportunity to … really clarify which kinds of cells are actually dying in Parkinson’s disease,” says Evan Macosko, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

The tricky part was that dopamine-making neurons in the substantia nigra are rare. In samples of postmortem brains, “we couldn’t survey enough of [the cells] to really get an answer,” Macosko says. But Abdulraouf Abdulraouf, a researcher in Macosko’s laboratory, led experiments that sorted these cells, figuring out a way to selectively pull the cells’ nuclei out from the rest of the cells present in the substantia nigra. That enrichment ultimately led to an abundance of nuclei to analyze.

By studying over 15,000 nuclei from the brains of eight formerly healthy people, the researchers further sorted dopamine-making cells in the substantia nigra into 10 distinct groups. Each of these cell groups was defined by a specific brain location and certain combinations of genes that were active.

When the researchers looked at substantia nigra neurons in the brains of people who died with either Parkinson’s disease or the related Lewy body dementia, the team noticed something curious: One of these 10 cell types was drastically diminished.

These missing neurons were identified by their location in the lower part of the substantia nigra and an active AGTR1 gene, lab member Tushar Kamath and colleagues found. That gene was thought to serve simply as a good way to identify these cells, Macosko says; researchers don’t know whether the gene has a role in these dopamine-making cells’ fate in people.

The new finding points to ways to perhaps counter the debilitating diseases. Scientists have been keen to replace the missing dopamine-making neurons in the brains of people with Parkinson’s. The new study shows what those cells would need to look like, Awatramani says. “If a particular subtype is more vulnerable in Parkinson’s disease, maybe that’s the one we should be trying to replace,” he says.

In fact, Macosko says that stem cell scientists have already been in contact, eager to make these specific cells. “We hope this is a guidepost,” Macosko says.

The new study involved only a small number of human brains. Going forward, Macosko and his colleagues hope to study more brains, and more parts of those brains. “We were able to get some pretty interesting insights with a relatively small number of people,” he says. “When we get to larger numbers of people with other kinds of diseases, I think we’re going to learn a lot.”