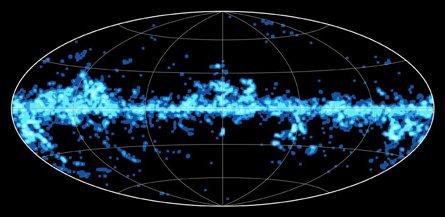

SEATTLE — The European Space Agency’s Planck spacecraft has identified the most massive galaxy clusters ever measured and the coldest clumps of material in the Milky Way. The frigid regions are sites of the earliest phases of star birth in the galaxy. The findings were unveiled January 11 at the winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society and at a news briefing in Paris.

The roughly 10,000 cold cores in the galaxy, many of them previously unknown, will enable astronomers to study the very beginnings of star formation, said Planck researcher Charles Lawrence of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Some of the cores are the coldest places ever recorded in the universe, with temperatures as low as 7 degrees above absolute zero, an indication that clumps of gas and dust, the raw material for making stars, has yet to gravitationally contract and heat these stellar nurseries.

The most massive clusters of galaxies detected by Planck weigh the equivalent of a million billion suns and lie within relatively nearby reaches of the universe. In tandem with more distant clusters found with ground-based instruments, these large aggregates of galaxies provide new insight about the evolution of galaxies as well as about the dark matter that holds these clusters together and dark energy, the mysterious entity that has accelerated the expansion of the universe, said John Carlstrom of the University of Chicago, who was not involved with the new study.

Although Planck’s main mission is to use sensitive microwave detectors to examine the faint microwave glow left over from the Big Bang, astronomers must painstakingly identify and subtract confounding emissions that the craft has recorded from foreground objects that radiate at those same microwave wavelengths. The new findings represent the first fruits of those labors.

Planck’s first complete map of the microwave background, which researchers hope will reveal new information about how the universe came to be, is expected in about two years.