A protein in mosquito eggshells could be the insects’ Achilles’ heel

New research on the bloodsuckers may one day help control their numbers

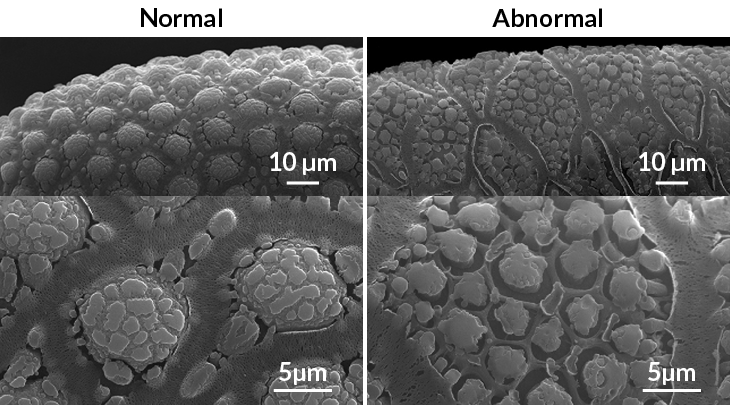

EGGCELENT Scientists have discovered a protein necessary for some mosquito eggs, such as these being laid by a Culex quinquefasciatus female, to properly develop eggshells.

Sean McCann/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)