Botanists have had the moss pulled over their eyes for more than a century when it comes to explosive spore discharge in a thick, soft plant that thrives in soggy places. Sphagnum’s spores don’t eject from their capsule because of the dramatic buildup of several atmospheres of pressure, but instead eject when the capsule cell walls dry and buckle, researchers report online and in an upcoming New Phytologist.

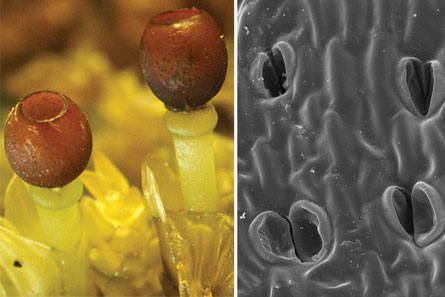

Sphagnum bears its spores in a perky, almost spherical, lidded capsule that sits atop a little stalk and may be reddish, brown or black. The capsule’s outer cells have tiny pores previously thought to be stomata that aid in gas exchange in plants. For generations, scientists also thought these pores contributed to the large buildup of pressure that, when released, supposedly blew off the capsule lid and flung the spores. Other plants such as brown algae and some fungi explosively release their spores, perhaps through hydrostatic pressure. But experiments with intact and pricked capsules suggest the pores are poseurs, actually pseudostomata that dry out and crumple but have nothing to do with gas exchange. As the cells dry, the capsule shrinks, ejecting its lid and flinging spores.

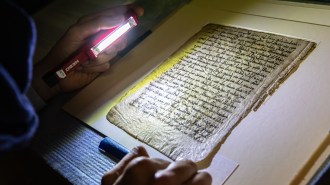

Silvia Pressel of Queen Mary University of London and her colleagues note that their study has shown “that a description of a biological process that has gone unchallenged and permeated the literature, been taught to thousands of botanists for more than a century, was ultimately a myth that could be overturned by simple experimentation.”