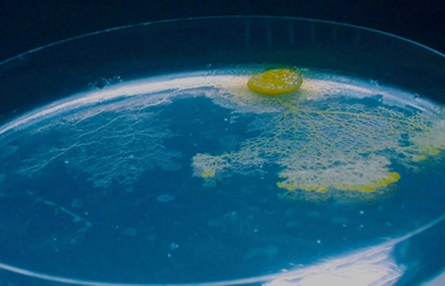

A dollop of living yellow ooze has aced a test of navigation, showing that you don’t really need a mind to make spatial memories.

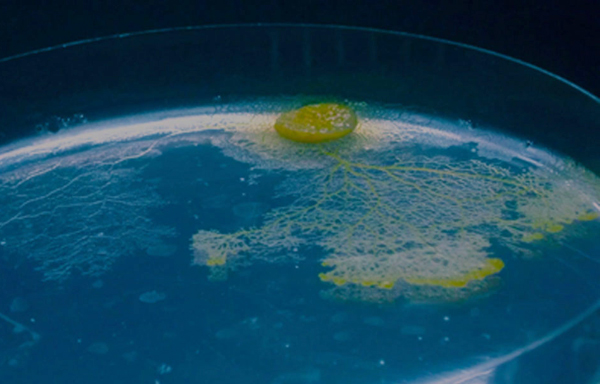

The egg-yolk-colored slime mold Physarum polycephalum is a single cell without any nervous system. But this blob of a creature uses its slime trails as a form of external spatial memory, says complex systems biologist Chris R. Reid of the University of Sydney. Smears of goo left behind as a slime mold crawls act as records of past paths. Given a choice, slime molds won’t crawl over their old slime, Reid and his colleagues found.

These simple external “memories” work quite well. When lured into a U-shaped dead-end in front of a sugar treat, slime molds were able to escape. Instead of just throbbing futilely against the closed end of the U or crawling around in circles, 23 out of 24 managed to ooze their way back out of the blind alley and creep to the treat by an outside route, Reid and his colleagues report October 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It’s the first time any spatial memory system has been found in an organism without a brain,” Reid says.

Ants, which Reid also studies, lay trails of scents as they scurry to food sources, and these scents can function as external memories of the whole colony. Ants do have brains though.

“A slime mold is just a little bag of goo,” Reid says, though with evident affection. The big crawling cells form when two spores of compatible types burst to life, meet and fuse. “It’s like a sperm cell meeting an egg,” Reid says. The resulting entity, called a plasmodium, engulfs debris and grows, with its nuclei dividing but no split in the cell. The little bits of living tissue making up this big cell pulse independently, speeding up or slowing down depending on what they nudge in their immediate environment. Like birds in a flock or fish in a school, pulsing bits can influence the motion of their immediate neighbors, a way of passing information through the organism. Although technically one cell, a slime mold plasmodium acts like a collective. “It’s alien stuff,” as Reid puts it.

As a brainless blob it can solve some remarkable problems. Given some time, a single slime mold oozing through a maze tends to consolidate into strands along the shortest paths. Given a surface with food flakes placed at important population centers or other points of interest, a slime mold eventually forms a pattern similar to road maps of real countries (such as Spain) or real subway systems (such as Tokyo).

Navigation by avoiding slime trails has been predicted for these remarkable organisms by Inbal Hecht of Tel Aviv University in Israel and her colleagues. Using a computer simulation of a cell wandering a maze, researchers predicted that avoiding past paths would be enough to succeed.

That’s basically what the new paper shows. “I am so thrilled to see it come true,” says Hecht.