Replacement for toxic chemical in plastics, receipts may be just as toxic

Mounting evidence suggests that BPS may cause the same health hazards as BPA

BAD TRADE Manufacturers may have ditched using the potentially toxic chemical BPA (bisphenol A) in common products such as receipts and plastic bottles in favor of an equally toxic relative, bisphenol S, new research suggests.

Stokkete/Shutterstock

Chemical tweaks aren’t enough to tame a possibly dangerous component of plastics, several new studies suggest.

Bisphenol S, or BPS, a common chemical in everyday plastics and papers, has the same toxic, hormone-disrupting effects in cells and animals as its older relative, bisphenol A, or BPA. The findings are the latest to raise doubts that BPS – or perhaps any other bisphenols – are a safer alternative to BPA. The studies also suggest that products labeled “BPA-free,” such as baby bottles, are not as free of health risks as consumers might expect.

In a study published February 26 in Environmental Health Perspectives, researchers found that BPS, like BPA, can boost heart rates and spur irregular heartbeats in female rats. In the Feb. 3 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers reported that BPS, like BPA, can alter brain development and behavior in zebrafish. The findings follow previous reports that BPS, like BPA, can mimic estrogen in humans and animals.

The potential human health hazards of BPS’s estrogen-mimicking remain unknown. But researchers have linked BPA to obesity, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, infertility, neurological problems and asthma.

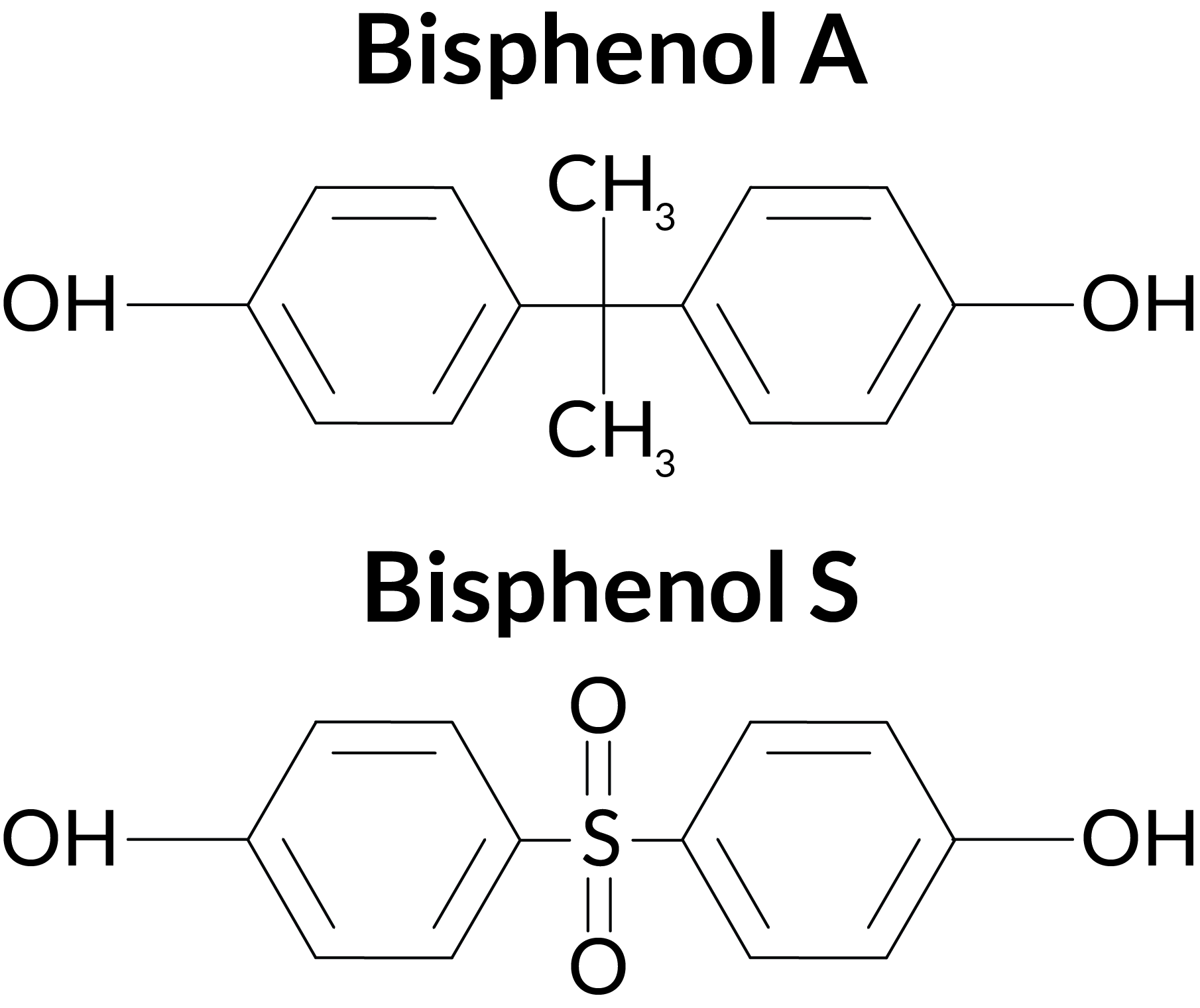

“Based on the (chemical) structural similarity, you’d expect that they’d be similar,” says environmental chemist Kurunthachalam Kannan. BPA consists of two identical, sturdy ring structures linked by carbon and hydrogen atoms. BPS has the same structure, except its identical rings are linked by sulfur with two oxygen atoms.

At the time, though, researchers had little data on what that exposure means for health. “The study of BPS has only recently started,” says pharmacologist Hong-Sheng Wang of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, lead researcher on the study that looked at the chemical’s effects on rat hearts. So far, Wang says, he’s amazed by how similar the effects of BPS are to those of BPA. “They are nearly indistinguishable, if not identical,” he says.

In Wang’s study, both chemicals altered how female rats’ heart cells generated the electrical pulses that power beating, causing the rats’ hearts to beat faster. When researchers added a chemical that mimics the effect of stress on the heart, both BPA and BPS could cause irregular heartbeats. If BPS acts similarly in humans, it might cause heart damage over time or put people with preexisting heart conditions or stressful lives at higher risk of heart disease.

The effects were seen only in female rats. Both BPA and BPS act like estrogen, Wang explains, and the males’ heart cells have a way of blocking that estrogen signal that the female rats’ cells don’t. It’s unclear if that would hold true in humans.

In the zebrafish study, researchers led by neuroscientist Cassandra Kinch of the University of Calgary in Canada exposed embryonic fish to low levels of BPS, similar to levels of BPA reported in nearby waterways.

The low doses of chemical spurred early development of nerve cells in a part of the brain that is responsive to estrogen, the hypothalamus. Such premature development could cause sweeping changes in brain function because development is a precisely timed, well-orchestrated process, Kinch says. When the fish grew up, they were hyperactive, zooming around their tanks in circles, she says. In humans, BPA exposure has also been linked to behavioral changes, including hyperactivity.

Despite the damaging data on BPA, it’s still widely used. In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration banned the use of BPA in baby bottles, but few other restrictions are in place in the United States. Likewise, the use of BPS and many other bisphenols is not restricted.

More animal studies are needed and quickly, says toxicologist Daniel Zalko of the French National Institute for Agricultural Research in Toulouse, France. It took years to collect data on BPA, he says, adding that he hopes it doesn’t take that long for BPS.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on March 10, 2015, to correct the levels of BPS that zebrafish were exposed to. The story was also updated to note that there are a few restrictions on BPA in the United States.