To makers of computer disk drives, the fainter the magnetic field a sensor can detect, the better. If data-reading heads can detect tinier data bits, which have weaker fields, manufacturers can cram more data into less disk space (SN: 4/3/99, p. 223).

Today, commercial read heads are made of layers of magnetic metals stacked into sandwich structures whose electrical resistance changes in response to a varying magnetic field. These so-called giant magnetoresistance heads change their resistance at room temperature by about 5 percent in the presence of a magnetic bit of data, says Stuart A. Solin of NEC Research Institute in Princeton, N.J.

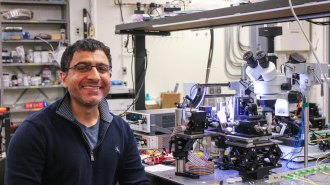

In the Sept. 1 Science, he and his colleagues unveil a new type of magnetoresistive device about the size of a pinhead. More like a traffic rotary for electrons than a sandwich, it could raise commercially useful magnetoresistance to new heights.

In more recent, unpublished experiments, “we’ve already obtained over 2,000 percent [resistance change] at magnetic fields relevant to read heads,” Solin told Science News. At high magnetic fields, the researchers have measured resistance change of up to 1 million percent.

Solin and his colleagues have coined a new phrase to describe their invention’s behavior: “extraordinary magnetoresistance.” To make a device demonstrating the effect, the researchers first deposit a ring of indium-antimonide, about a micrometer thick, onto a gallium-arsenide plate. Then, they fill its center with gold.

In the absence of a magnetic field, current passes handily through the gold, so the resistance is tiny. However, a magnetic field exerts a perpendicular force on moving electrons. As the researchers raise the magnetic field, this deflection forces more current into the indium-antimonide, where resistance is high.