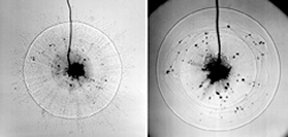

With a flash and a bang, a pellet of explosive detonates in a cavernous laboratory on the outskirts of the Pennsylvania State University campus. The explosive, triacetone triperoxide (TATP), is the one that terrorists reportedly used in their attack on the London subway in July 2005. Minutes after the lab explosion, engineers—some with bulky ear-protection gear still in place—stare at a laptop screen as they scan frame after frame of high-speed images. Beyond the flame and flying debris, the scientists focus on the ephemeral supersonic shock waves that emanate from the blast. The waves appear in the pictures as rings, ripples, or streaks.

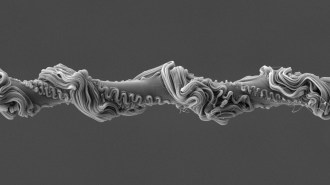

In studies by the Penn State investigators and others, a rare marriage of technologies is yielding unprecedented visualizations of the shock waves created by a variety of phenomena. The researchers have combined modern high-speed digital video with techniques known as shadowgraphy and schlieren imaging, which date back centuries.

In the 19th century, scientists used basic forms of the techniques for detecting flaws in lenses or for visualizing shock waves made by bullets. Today, researchers can study not only the meters-wide blast of a lump of TATP but also kilometers-long pressure patterns from the supersonic flight of an aircraft.

Similar visualizations are illuminating the complex behavior and destructive impacts of shock waves in past and potential aviation disasters, says Penn State’s Gary S. Settles, who heads the lab in University Park. The investigators have also been capturing extraordinary footage of gunshots, and their analyses may alter the way in which weapons experts interpret some types of forensic evidence.

“A good fluid dynamicist knows you have to see the flow to know what’s going on,” says physicist Leonard M. Weinstein of the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va., who pioneered some of the visualization techniques.

Smoke and mirrors

A simple optical effect underlies both shadowgraphy and schlieren imaging: Light rays bend, or refract, at the boundaries between air masses of different densities. The same phenomenon causes the twinkle of stars and the distorted appearance of objects on the far side of a patch of hot pavement.

The more rudimentary of the two methods, shadowgraphy, requires only a brilliant light source, an air disturbance, a glossy surface on the opposite side of the disturbance, and a camera to take the picture.

Consider a shadowgraph of the air above a heater. Rays of light bend as they pass through rising air currents. So, some parts of the glossy surface receive more light than they would in the absence of the air disturbance, and others receive less. The camera captures the image as a set of density ripples.

More sophisticated and sensitive than shadowgraphy, schlieren imaging has typically required a bright light, a pair of parabolic mirrors—one in front of and the other behind the air disturbance—and a sharp-edged obstacle. One mirror collects light rays from the lamp and reorients them into a beam of parallel rays aimed at the disturbance. The other mirror collects the projected image and focuses it onto a spot. There, the sharp obstacle blocks many of the divergent rays, deepening the dark areas in the density ripples. Finally, the remaining light goes to a screen or into a camera that records the image.

Because of the focusing and the heightened contrast caused by the obstacle, schlieren imaging can visualize subtler fluctuations than can shadowgraphy, Settles says. On the other hand, schlieren systems typically can make images only of subjects that fit within the light beam created by the first mirror.

For decades, the prohibitive cost of large, high-quality mirrors made for use in telescopes relegated most schlieren imaging to small-scale phenomena such as bullets breaking the sound barrier and miniature models of aircraft in wind tunnels.

Then, in the early 1990s, Weinstein figured out ways to make schlieren pictures without mirrors. Other researchers had considered some of these methods but didn’t implement them, Weinstein says.

He illuminated subjects with light bounced off a backdrop of the light-reflecting material, called retroreflective sheeting, that’s used in highway signs. Weinstein added vertical black stripes. He used a large-format camera, rather than a mirror, for focusing images. A transparent photographic negative, adorned, like the sheeting, with vertical black stripes sits in front of the film inside the camera. Because the black stripes of the negative exactly fill the spaces between the stripes on the camera’s image of the backdrop, the interlocking patterns cut off nearly all light rays except those bent by refraction.

That work led to the unprecedented, full-scale imaging of a range of previously invisible phenomena, including the shock waves created by blasts, flows of gases from industrial equipment, and wavy plumes of air around people, ovens, and air conditioners.

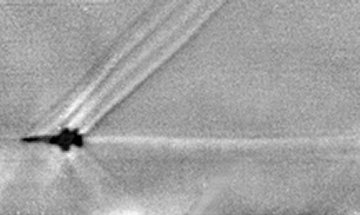

Besides opening indoor schlieren systems to large subjects, Weinstein invented a technique for taking schlieren shots outdoors and observing a truly huge phenomenon—the sky-filling shock waves from supersonic aircraft in flight.

For that last feat, a camera-equipped, sun-tracking telescope observes through a slit a sliver of the sky that includes the edge of the sun. As an aircraft flies through that sliver, the camera composes an image of the plane and the sky above and below it from successive views through the slit.

Because refraction causes more or less of the sunlight in the sliver to pass through the slit, the schlieren image reveals the otherwise invisible shock waves streaming away from the aircraft. “I’ve taken one [schlieren image] where the shock wave reached 12,000 feet below the plane,” Weinstein notes.

Having a blast

Working with Weinstein a decade ago, Settles and his colleagues built the world’s largest indoor schlieren-imaging system. It’s in an old warehouse on the outskirts of the Penn State campus. The lab’s retroreflective backdrop, which hangs on one wall, measures about 5 meters by 5 m.

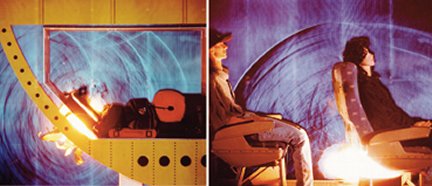

The jumbo size of that setup has enabled the Penn State team to undertake schlieren observations of simulations of bomb blasts in passenger aircraft. In tests funded by the Federal Aviation Administration, the researchers constructed a full-scale mockup of a portion of an aircraft passenger cabin and observed the effects of explosions under a passenger seat. They also recorded shock waves emerging from suitcases after a blast in a 60 percent mock-up of an aircraft luggage compartment.

The studies, which the team described in 2003, provided the first direct, visual evidence of the shock-wave reverberations that could cause fuselage damage far from the site of a blast within a plane. The images have led to “useful information for the future so that aircraft can be designed to better withstand an explosion,” Settles says.

Recently, the Penn State team has taken remarkable pictures of firearms discharging that show much more than typical schlieren images do. Whereas the old method typically showed shock waves from the bullet and in the immediate vicinity of a muzzle, the newer, wide-view schlieren pictures also reveal shock waves and evidence of hot combustion gases extending for several meters.

“We all knew that that stuff was there, but [Settles] was one of the first to visualize it at that size. Previously, you could only look at a section of it,” says Andrew Davidhazy of the Rochester (N.Y.) Institute of Technology. He teaches shadowgraphy and schlieren techniques.

By depicting how shock waves and combustion-gas clouds interact with nearby objects, including the shooter, images could someday enable criminologists to more accurately link aspects of shootings, such as the weapon used and the distance at which it was fired, to powder burns or other gunshot effects on victims and suspects, Settles says. Davidhazy agrees: “The more information you can get about a [fired] round, the better your forensic analysis is going to be.”

Fast forward

Shadowgraphy went big-time earlier than schlieren imaging did, but until recently, large-scale shadowgraphy didn’t catch on. In the late 1950s, high-speed-photography pioneer Harold Edgerton demonstrated large-scale shadowgraphy by upgrading to a large, retroreflective screen. Using a roughly 1-m-by-2-m screen, rather than one the size of a dinner plate, he photographed the explosion of a dynamite cap.

More recently, Settles and his colleagues ushered shadowgraphy into the 21st century by projecting images onto an even bigger screen. They also record the images with a high-resolution digital video camera capable of taking thousands of 1-microsecond-long exposures each second.

A particular advantage of digital video in place of bulky film cameras is that shadowgraphy setups have suddenly become portable. The screen, now the bulkiest piece of the equipment, rolls up for transport.

Putting that road-worthiness to the test for the first time, the Penn State team took its gear to a U.S. Army lab in Aberdeen, Md., last summer to video explosions in aircraft-luggage containers, as part of a study for the Transportation Security Administration. Using protective shielding for their equipment and themselves, the researchers made images showing how the containers responded to explosions. They haven’t yet reported their results.

Settles described that fieldwork and other recent shadowgraphy developments in September 2005 at a visualization conference in Queensland, Australia.

Next, Settles’ team intends to use shadowgraphy to image shock waves unleashed in a full-scale, exploding airplane. The researchers have to wait until federally funded aviation engineers, responsible for fortifying aircraft against threats such as terrorist bombs and fuel-tank explosions, detonate charges in a retired Boeing-747 or another big jet.

The Department of Homeland Security periodically conducts such tests to assess recent antibomb modifications on commercial airliners, but the date for the next experimental blast hasn’t been set, Settles says.

For a test of a whole plane, Settles’ team would set up its screen so that shock waves could be observed emerging from the side of the plane. If the test is on a cross-section removed from the fuselage, as it often is, the researchers would place their light and screen on one side of the open portion of the fuselage and put their camera on the other to observe shock wave reverberations, Settles says.

No previous test has visualized shock waves during an explosion in an actual airplane, he notes. But his team is now ready with the first-ever, simple, portable means to do so.