A new treatment mimics the pain-blocking mechanism of acupuncture but offers longer-lasting pain relief, at least in mice.

Injections of an enzyme called PAP into an acupuncture point behind the knees of mice relieved pain caused by inflammation for up to six days, Julie Hurt and Mark Zylka of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill report online April 23 in Molecular Pain. That’s almost 100 times longer than pain relief from acupuncture, which typically lasts about 1½ hours.

Long-lasting pain relief “is truly important, clinically,” says Maiken Nedergaard, a neuroscientist at the University of Rochester in New York. She and colleagues previously demonstrated that inserting and manipulating acupuncture needles causes the body to release a chemical called adenosine. Adenosine acts as a local anesthetic to slow down pain messages sent to the brain, she says.

“The beauty of Mark’s study is that it takes advantage of the molecular mechanism of acupuncture and improves upon it,” Nedergaard says.

Zylka had already been studying PAP, which stands for prostatic acid phosphatase, when Nedergaard’s research on the release of adenosine during acupuncture was published. The study gave him the idea that boosting adenosine at acupuncture points, which are located where nerves contact muscle, could be a localized way to treat pain. Adenosine lasts only minutes in the human body, so injections of the chemical itself were not an option.

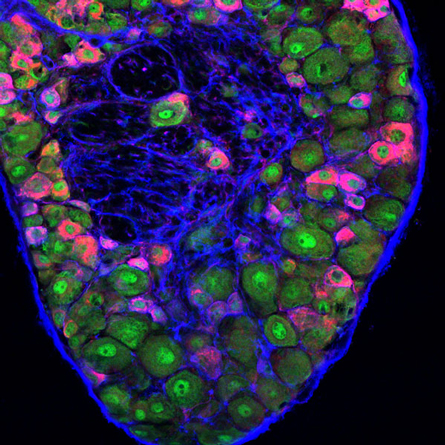

But Zylka knew that PAP, which produces adenosine by breaking down adenosine monophosphate or AMP, lasts a long time and can continue churning out adenosine as long as it has a supply of AMP. Muscles are a ready source of AMP, itself a breakdown product of a molecule called ATP, which cells use for energy. So Zylka and Hurt decided to inject PAP into a space behind the knee, called the popliteal fossa. In people, doctors inject anesthetics at that spot, which encompasses the Weizhong acupuncture point.

PAP injections in mice with inflamed paws made the limbs less sensitive to heat and poking — but didn’t cause muscle weakness or other discernible side effects, the researchers found.

Other scientists have postulated that acupuncture releases feel-good chemicals called endorphins, which work all over the body. But the new study helps cement the idea that acupuncture really works locally, Nedergaard says.

Not only does PAP relieve inflammatory pain longer than acupuncture does, it also relieves nerve pain in mice, testing showed. Clinical studies in people have found that patients with nerve pain get worse after acupuncture, says Jon Levine, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“Maybe what [Zylka] starts with is the core of what acupuncture does, but then goes beyond to do something acupuncture doesn’t do,” Levine says.

Zylka says that a company may soon start testing the enzyme as a pain reliever for humans.