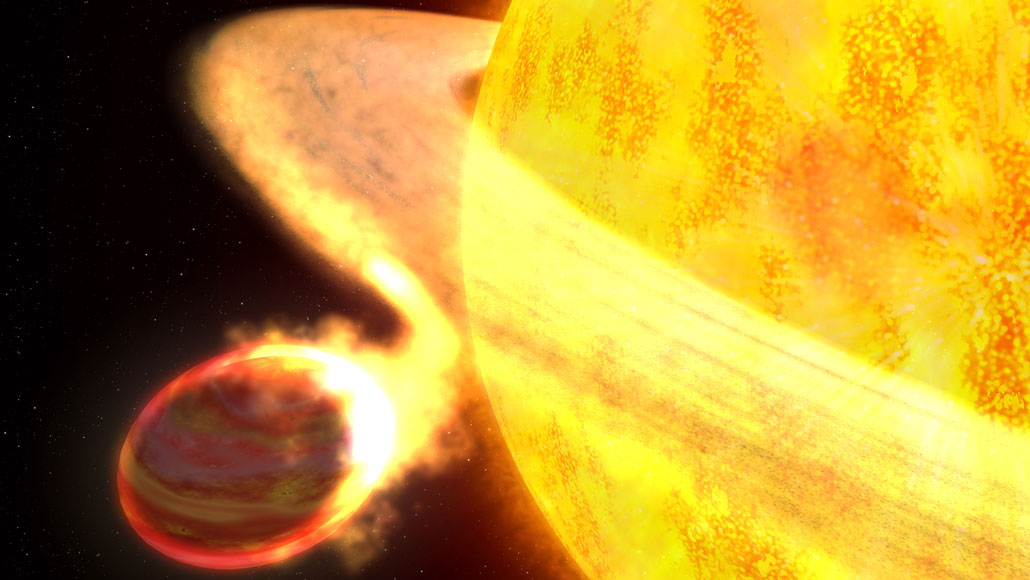

Planets that orbit close to stars, as in this artist’s illustration, could get swallowed up as the star ages.

G. Bacon, ESA, NASA

- More than 2 years ago

When giant stars eat giant planets, their starlight may shine a bit less brightly. That dimming could affect how astronomers measure distances across the universe — and possibly even put past measurements in doubt.

“You would think the planet would be a small perturbation to the star,” says astrophysicist Licia Verde. “It turns out that it’s not.” Those perturbations may even help explain why estimates for how fast the universe is expanding disagree, Verde and her colleagues argue in a paper posted March 25 at arXiv.org.

When stars similar in mass to the sun burn through most of the hydrogen in their cores, their outer layers puff up until the stars are hundreds of times their original sizes, becoming red giants. At a certain core density, red giants were all thought to reach the same peak brightness.

That uniform brightness has helped astronomers estimate cosmic distances. It’s hard to know how far away a star is without knowing its intrinsic brightness — a star may appear dim because it’s very far away, or just because it’s dim, or both. Because red giants always peak at a certain brightness, they can act as distance markers across the universe, giving astronomers cosmic landmarks to measure the space between Earth and far-off galaxies.

Astronomers have seen signs that red giants engulf nearby planets while expanding (SN: 12/21/11). Verde and astrophysicist Raul Jimenez, both of the University of Barcelona, along with Uffe Gråe Jørgensen, an astrophysicist at the University of Copenhagen, wondered if those planetary meals could change how the star shines. If so, that would mean a red giant’s peak brightness is a little less reliable as a uniform constant than previously thought.

There are a few different ways a planet could change the star’s brightness, the team reasoned: If the planet gave the star’s core more matter to burn, that could turn up the lights, making the star seem nearer than it is. Or eating a planet could stir up the star’s outer gas layers in a way that made light particles, or photons, bounce around more within the star’s atmosphere. Then fewer photons would escape, and the star would appear dimmer.

Computer simulations to test these scenarios would be slow and expensive. So the team did some rough calculations to see if simulations would even be worth it. And in fact, those calculations showed that the extra mass from ingesting a planet doesn’t matter very much on its own. But if a large enough planet plunges into the star at high speed, it could stir up the star’s outer layers “like a spoon in a teacup,” Jimenez says. In that scenario, the star’s brightness drops by up to 5 percent, the team estimates.

That slight shift could make a big difference to cosmology, and particularly to estimates of the universe’s expansion rate — a number known as the Hubble constant. To measure the Hubble constant, astronomers need to know precisely how fast cosmic objects appear to be receding thanks to cosmic expansion, as well as how far those objects actually are from Earth.

So astronomers use objects with known luminosities as so-called “standard candles” to help determine cosmic distances. Red giants are one example; supernovas and stars called Cepheids are others.

But measurements using different candles have resulted in different estimates for the Hubble constant. Another method using details of how matter was distributed in the very early universe gave yet another Hubble constant value. The discrepancies have led to a crisis in cosmology: Either some of the measurements are wrong, or the universe behaved differently in its early epochs than it does today. That would mean long-held ideas about how the universe formed and evolved may need revision (SN: 7/30/19).

“People believe [the mismatch] could be a signature of new physics,” Jimenez says. “That’s the excitement.”

Cosmologist Wendy Freedman of the University of Chicago, who measured the Hubble constant using red giant stars, thinks more detailed studies are needed to figure out if planetary meals are a problem for the Hubble constant estimate. Even if some stars shine less brightly because they’ve ingested a planet, that won’t make a difference if the same thing is happening in every galaxy, she notes.

Astronomers also have used both Cepheids and red giants in a single galaxy to measure that galaxy’s distance from Earth, and the two methods give the same answer. That suggests cosmologists might not need to worry about red stars’ dimming after devouring planets.

“Theoretical components and constraints you can get from existing observations suggest that, at the moment, this is not a serious issue,” Freedman says.