The steroid dexamethasone is the first drug shown to reduce COVID-19 deaths

The drug might save one of every eight people on ventilators and one of 25 on oxygen

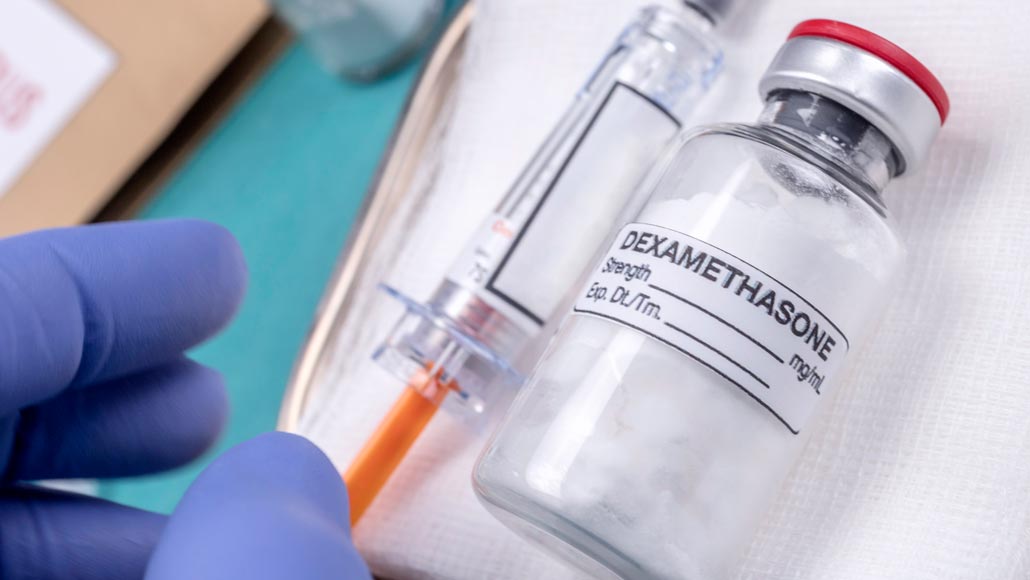

Given as intravenous injection, the steroid dexamethasone reduced the number of deaths among COVID-19 patients on ventilators, scientists say in a news release.

Digicomphoto/iStock/Getty Images Plus

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

A low-cost steroid may save the lives of some people who are on ventilators or supplemental oxygen because of COVID-19, preliminary data from a large clinical trial suggest.

Dexamethasone, a steroid in use for decades, reduced deaths of COVID-19 patients on ventilators by about a third compared with standard care, researchers reported in a news release June 16. Deaths of COVID-19 patients on supplemental oxygen were reduced by about 20 percent. Researchers found no benefit for hospitalized patients who didn’t need extra oxygen.

If the results hold up to scrutiny once scientists have a chance to review the full data, the drug would be the first to reduce the risk of death from the disease. For many patients who wind up in the hospital with COVID-19, “question one is, ‘Will I survive?’ and question two is ‘How long will I have to stay in hospital?’ This is the first drug that says, yes, we can increase your chances of survival,” says Martin Landray, a cardiologist at the University of Oxford. Another drug, remdesivir, has been shown to shorten recovery time for seriously ill patients (SN: 5/13/20).

The new finding was based on outcomes of 2,104 patients taking 6 milligrams of dexamethasone once a day for 10 days either as a tablet or by intravenous injection and 4,321 people not taking the drug. The study was stopped early once a steering committee felt enough patients had been enrolled in this segment of the study to determine whether the drug worked or not. Landray and colleagues discovered that taking dexamethasone could prevent one death for every eight patients on ventilation, and one death for every 25 patients needing extra oxygen.

“It’s not a fix. It’s not a cure. It’s not a miracle, but it is really, really useful,” Landray says. He expects doctors around the world will embrace the therapy. He says that the United Kingdom’s National Health Service may soon declare dexamethasone the standard treatment for people on ventilators because of COVID-19.

“These are potentially very exciting data,” says Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious diseases doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. He has helped write COVID-19 treatment guidelines for the U.S. National Institutes of Health and for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, but says he will wait until he sees the full report to decide whether the results warrant changing treatment of severely ill patients. “Right now we have very limited information, but if it’s borne out it could be really exciting.”

Although the results are important for treating the sickest patients with COVID-19, those patients represent only about 5 percent of people diagnosed with the coronavirus, Gandhi says. “It’s not steroids for all.”

For the majority of patients, the drug probably would not do any good and may even do harm. Dexamethasone and other steroids dampen the immune system’s response to invading organisms, and have been shown to make viral infections, such as influenza and SARS worse. Researchers thought that if steroids worsened SARS, it might do the same for SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Treatment guidelines suggest doctors not use steroids against the novel coronavirus.

The way the results were released has some scientists worried that they may not hold up. “We’ve all seen preprints and press releases about other potential therapies that have not borne out to be true,” says Brian Garibaldi, director of the biocontainment unit at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Landray says he understands the criticism, but felt it was important to “get the results out into the public domain so that they’re no longer my little secrets, the world at large can see them and make their decisions.”

He and colleagues are writing a scientific paper with more details, but it will take time for the study to be reviewed and published. Meanwhile, he says, “the drug is already sitting in hospitals now — it doesn’t cost much money and the benefits are really obvious — and it can be used worldwide and you’re in the middle of a pandemic.”

Garibaldi says he’s hopeful that the results will hold up. “Certainly to have something that would reduce mortality would be a game changer,” he says, but doctors are unlikely to alter treatments for their patients based on the limited data presented. “When I go into the ICU next week, I don’t plan on using dexamethasone unless I can see the data and we can discuss it as a critical care community.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.