In the mid-1980s, at the height of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union each had thousands of nuclear warheads, along with a multitude of aircrews and missiles, sitting on red alert to carry those bombs to their targets at a moment’s notice. The philosophy of mutual assured destruction—the notion that any use of nuclear weapons would trigger a full-fledged exchange that neither nation would survive—may have deterred any use of such bombs since World War II.

As devastating as a nuclear war between superpowers would have been, the after-effects probably would have been worse. In the 1980s, scientists estimated that a war in which each superpower used half its nuclear arsenal would have destroyed the upper atmosphere’s ozone layer and, by filling the skies with dust and smoke, decreased temperatures at ground level in some regions as much as 40°C for up to a decade. Scientists and antinuclear advocates dubbed this chilling result nuclear winter. The lengthy famine sure to follow probably would have killed more people than the brief war would have.

Today, the Cold War is over, the Soviet Union is no more, and the United States and Russia are dismantling their nuclear stockpiles. Together, the two countries now maintain about 20,000 weapons, less than a third of the number that sat at the ready in 1986.

But there’s no reason to celebrate just yet, new studies suggest.

“While there’s a perception that a nuclear build down by the world’s major powers in recent decades has somehow resolved the global nuclear threat, a more accurate portrayal is that we’re at a perilous crossroads,” says Brian Toon, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and one of the researchers who first floated the idea of a nuclear winter.

Today’s threat stems from a variety of factors, Toon and his colleagues say. Nations are joining the nuclear club with unnerving regularity, others are suspected of having ambitions to do so, and dozens more have enough uranium and plutonium on hand to build at least a few Hiroshima-size bombs. The leaders of some of these nations may have no qualms about using such weapons, even against a nonnuclear neighbor. Increasingly, people are living in large cities, which make tempting targets.

Finally, the results of today’s climate simulations—which are much more sophisticated than those that were available in the 1980s—suggest that even a nuclear exchange of just a few dozen weapons could cool Earth substantially for a decade or more.

The current combination of nuclear proliferation, political instability, and urban demographics “forms perhaps the greatest danger to the stability of human society since the dawn of man,” warns Toon.

Recognizing this danger, on Jan. 17, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the minute hand on its “doomsday clock” 2 minutes closer to midnight. “It’s been 60 years since nuclear weapons have been used in war, but the psychological barriers that have helped limit the potential for the use of nuclear weapons in this country and others seems to be breaking down,” says Lawrence M. Krauss, a member of the group and a physicist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Join the club

In 1950, there were two nuclear powers—the United States, whose Manhattan Project developed the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II, and the Soviet Union, which conducted its first nuclear test in August 1949. By 1968, when the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons was proposed, France, the United Kingdom, and China had joined the pack. Outside that treaty from its beginning, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have developed weapons and conducted tests. Also, Israel is widely suspected of possessing nuclear weapons.

A handful of nations once possessed nuclear weapons but abandoned them. Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan inherited warheads when the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991 but have since transferred those weapons to Russia. South Africa has admitted constructing, but later disassembling, six nuclear devices, possibly after one test, says Toon.

In total, he says, at least 19 nations are now known to have programs to develop nuclear weapons or to have previously pursued that goal. Many more nations, through their power-generating and research nuclear reactor programs, have the raw materials for constructing nuclear devices, he and his colleagues reported in December 2006 at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. Those raw materials aren’t scarce: At least 40 nations have enough uranium and plutonium on hand to construct substantial nuclear arsenals.

Disturbingly, some of the nations with abundant bomb material have or have recently had strained relations with their neighbors. At the end of 2003, for example, Brazil probably had enough plutonium on hand to make more than 200 Hiroshima-size bombs, while its former rival Argentina could have produced 1,100 such bombs. Although North Korea probably has enough nuclear material to fabricate only a handful of the devices, South Korea has enough plutonium to construct at least 4,400. Pakistan could make 100 or more nuclear bombs, and its neighbor India could put together well over 10 times as many, the researchers estimate.

Today, at least 13 nations operate facilities that enrich uranium, plutonium, or both, says Toon. Altogether, 45 nations are known to have previous nuclear weapons programs, current weapons stockpiles, or the potential to become nuclear states.

Moving targets

In the late 1970s, researchers analyzed a variety of scenarios describing a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union. In some simulations, analysts presumed that either side’s primary targets would be military facilities rather than population centers. In such an attack, between 2 million and 20 million people would die—largely as a result of radioactive fallout, not the blasts. At the other extreme, a full-scale Soviet attack that included U.S. economic targets, such as cities and ports, would use thousands of weapons and kill up to 160 million people.

Neither of those scenarios accurately portrays a nuclear war between regional rivals. A new nuclear power probably wouldn’t have enough weapons on hand to target its opponent’s entire military infrastructure. Therefore, “a small country is likely to direct its weapons against population centers to maximize damage and achieve the greatest advantage,” Toon notes. Leaders of a fledgling nuclear power probably wouldn’t believe that they could survive an opponent’s first strike. Moreover, a small nuclear power might be more inclined than a superpower to strike first.

Because of recent growth and shifts in the world’s population, more people are living in urban areas with more than 10 million residents, says Richard P. Turco, an atmospheric scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. Such megacities often have a densely populated urban core full of flammable materials: schools, offices, shopping malls, gas stations, vehicles with their complement of motor oils and fuels, and even the asphalt paving.

The brief but intense thermal pulse of a nuclear explosion immediately ignites any combustible material nearby. “It’s like a bit of sunlight brought down to Earth,” says Turco. A Hiroshima-size nuclear bomb packs the same explosive punch as about 13,500 metric tons of TNT and can cause urban fires that release more than 1,000 times the energy of the bomb itself. The bomb that destroyed Hiroshima scorched an area of about 13 square kilometers.

On average, about 11 metric tons of flammable material are associated with each resident of a megacity, Turco and his colleagues reported at the San Francisco meeting. The team used population data to estimate not only how many people would die but also how much smoke and soot would be produced as the result of any given nuclear exchange.

If a Hiroshima-size bomb were to explode in the sky above each of the 50 most densely populated areas of the United States, more than 4 million people would die, the researchers estimate. Exploding 50 bombs over both India and Pakistan could cause 12.4 million and 9.2 million deaths, respectively.

The firestorms triggered by such nuclear volleys would produce millions of tons of smoke and soot, Turco notes. Lumber in buildings would generate about 40 percent of the soot. The rest would result from the combustion of petroleum products such as motor fuels, plastics, and asphalt roofing. Because soot from those sources repels moisture, water vapor in the air wouldn’t condense on the particles. Therefore, rain wouldn’t efficiently cleanse the air, and the soot would remain aloft longer than soot from a natural fire would.

Up, up, and away

Tracking and monitoring the smoke plumes from natural wildfires provides researchers with a notion of how soot and other small particles from nuclear firestorms would spread throughout the atmosphere, as well as data about the storms’ possible effects on climate.

In general, high-flying particles of ash and soot either absorb sunlight or scatter it. Some of that energy heats nearby particles, while some bounces back into space. That process cools Earth’s surface while heating the atmosphere around the particles, says Mike Fromm, an atmospheric scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. The smoke from small wildfires typically rises only a few kilometers and stays within the troposphere, the layer of the atmosphere where most weather occurs. Within the past decade, however, scientists have recognized that the plumes from major blazes can reach the stratosphere.

Take, for example, the Chisholm fire, a 7-day blaze that consumed almost 1,200 km2 of timber in central Alberta in May 2001. The thick plume of smoke from that fire was the tallest ever observed, Fromm reported at the San Francisco meeting. Satellite observations of particles in the atmosphere in late June indicated that smoke had reached the stratosphere and spread over much of the Northern Hemisphere, reaching as far south as Hawaii and as far north as Svalbard, a Norwegian island in the Arctic Ocean. Similarly, smoke from a large fire surrounding Canberra, Australia, early in 2003 spread over much of the Southern Hemisphere.

Smoke and soot from huge blazes generally reach the stratosphere in a two-stage process, says Eric J. Jensen, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif. First, the hot, buoyant air carries the particles to heights of around 10 km and spreads them into a layer hundreds of meters thick. Then, solar radiation heats the dark particles further, warming the surrounding air, which slowly rises higher and carries the particles with it.

Results of a recent computer analysis illustrate the phenomenon, says Jensen. He and his colleagues simulated a high-altitude smoke plume from a summer fire by modeling 10,000 metric tons of smoke particles dispersed in a 500-m-thick, 100-km square layer of atmosphere at a height of 9 km. After 1 hour of simulation time, solar radiation warmed the particles and the air, providing an updraft of about 1 m per second. After 10 hours, most of the smoke reached an altitude of 11 km, putting it into the stratosphere.

Chill in the air

Although wildfires are a prodigious source of small particles in the atmosphere, the largest suppliers of what scientists call natural aerosols are major volcanic eruptions. The sun-blocking effect of the minuscule bits of volcanic ash and droplets of water and sulfuric acid can cool Earth’s climate significantly for months or even a year or two. The aerosols are especially persistent if they reach the stratosphere, where they waft above most weather and therefore aren’t efficiently cleansed from the atmosphere.

Once the volcanic plumes spread at high altitude, they typically prevent no more than 1 percent of the sun’s light from reaching Earth’s surface (SN: 2/18/06, p. 110: Available to subscribers at Krakatoa stifled sea level rise for decades). But high-flying smoke and soot in the aftermath of even a limited nuclear war—one with as few as 100 Hiroshima-size bombs—would be much denser than that and the materials would block the sun as effectively as the thick clouds of a stormy day do, says Luke Oman, an environmental scientist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. He and his colleagues used computer models to simulate the effects of just such a war between India and Pakistan.

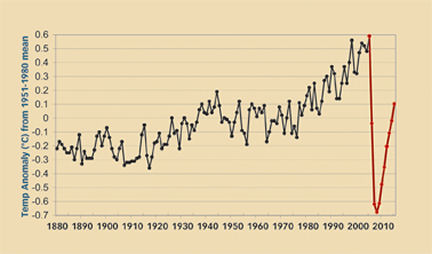

If those bombs exploded over the most-populated areas of the nations, more than 5 million metric tons of smoke and soot would soar into the sky. Most of those particles would stay aloft for more than 6 years, says Oman. On average, the temperature at Earth’s surface would drop around 1.25°C for up to 3 years—about four times the short-term cooling effect resulting from the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. After 10 years, the global average temperature would still be 0.5°C below normal.

Those temperature decreases may seem no more than a slight chill, but they’re substantial, says Alan Robock, also of Rutgers University. Temperatures in the first few years after a 100-bomb India-Pakistan war would be cooler than during a centuries-long cold spell called the Little Ice Age, which ended during the mid-1800s. Average global temperatures were at that time between 0.6°C and 0.7°C below what they are today, and glaciers advanced in mountainous regions worldwide.

While temperatures at Earth’s surface would drop, those in the stratosphere would increase by 30°C or more for at least 3 years, says Michael J. Mills, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder. At those higher temperatures, the large quantities of nitrogen oxides formed during the nuclear explosions—when nitrogen in the air literally burns—would destroy high-altitude ozone at rates much higher than normal, he notes.

In the team’s simulations, between 50 and 70 percent of the ozone high over polar regions disappeared. Losses were lower over the tropics, but ozone there still decreased by at least 10 percent. A 100-bomb nuclear exchange would create “a global ozone hole,” says Mills. Because animals are adapted to the particular level of ozone protection that’s normal for their latitudes, any significant ozone loss could be catastrophic, he suggests.

“Only disarmament can prevent the possibility of a nuclear environmental catastrophe,” Robock grimly told the audience at the San Francisco meeting.

That a nuclear winter could be triggered by a regional war is particularly ironic, adds Stephen Schneider, a climate scientist at Stanford University. A few decades ago, people were afraid that an all-out nuclear war between superpowers would trigger a climate catastrophe. Today, the United States and Russia could simply end up as helpless bystanders—who would nevertheless be left out in the cold.