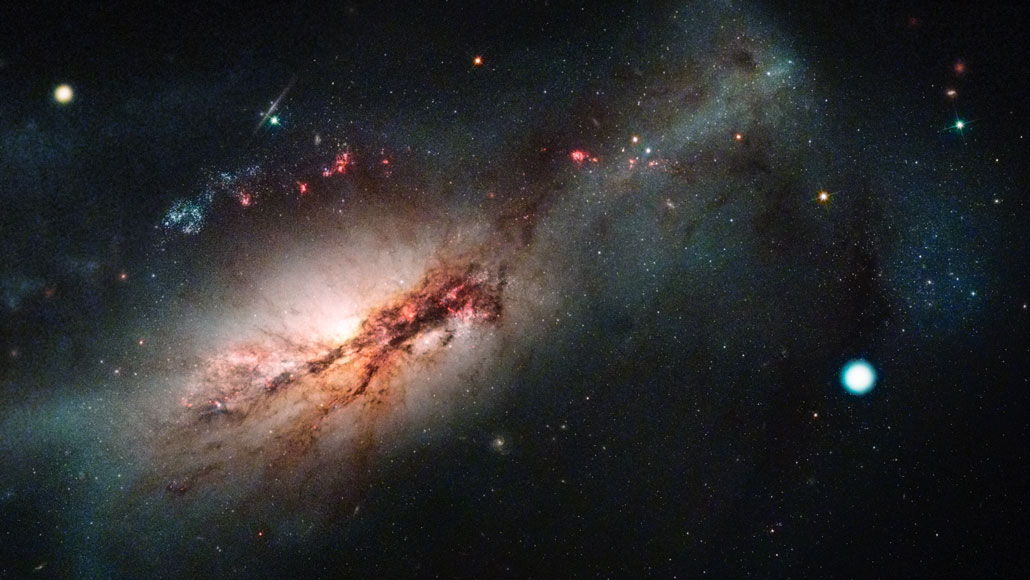

Confirming a decades-old prediction, scientists found the first clear example of a type of stellar explosion called an electron-capture supernova (large white dot at right).

J. DePasquale, Las Cumbres Observatory, NASA, STScI

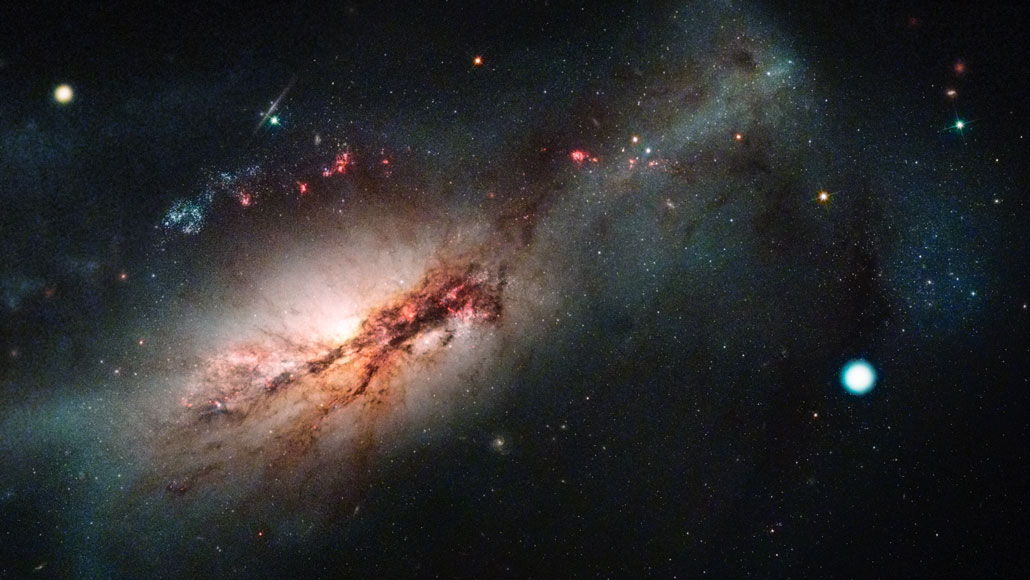

Confirming a decades-old prediction, scientists found the first clear example of a type of stellar explosion called an electron-capture supernova (large white dot at right).

J. DePasquale, Las Cumbres Observatory, NASA, STScI