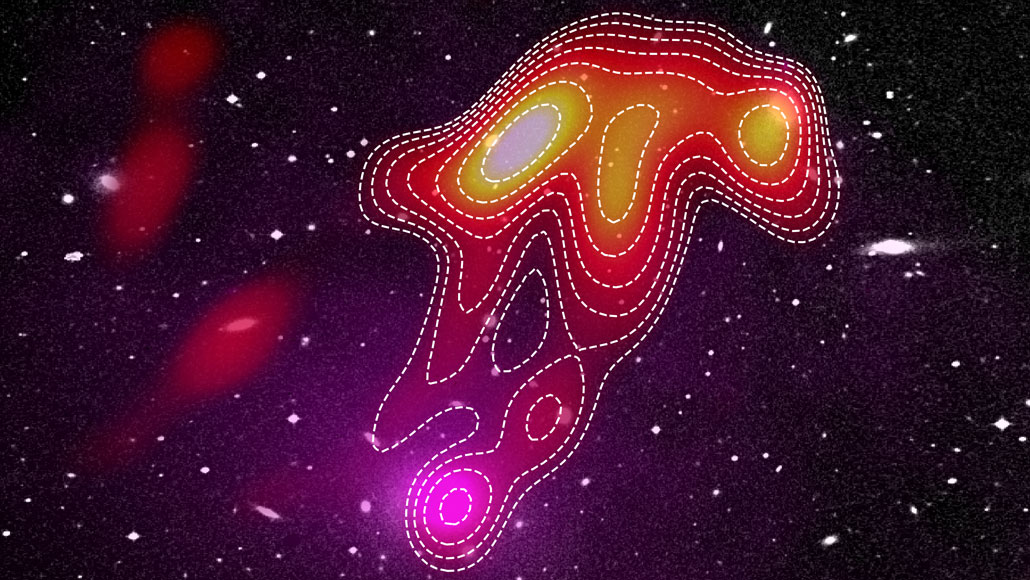

Low-frequency radio waves (red, orange, yellow, white) outline a huge “jellyfish,” 1.2 million light-years across, in galaxy cluster Abell 2877, whose center emits X-rays (magenta).

Torrance Hodgson, ICRAR/Curtin University

Something’s fishy in the southern constellation Phoenix.

Strange radio emissions from a distant galaxy cluster take the shape of a gigantic jellyfish, complete with head and tentacles. Moreover, the cosmic jellyfish emits only the lowest radio frequencies and can’t be detected at higher frequencies. The unusual shape and radio spectrum tell a tale of intergalactic gas washing over galaxies and gently revving up electrons spewed out by gargantuan black holes long ago, researchers report in the March 10 Astrophysical Journal.

Spanning 1.2 million light-years, the strange entity lies in Abell 2877, a cluster of galaxies 340 million light-years from Earth. Researchers have dubbed the object the USS Jellyfish, because of its ultra-steep spectrum, or USS, from low to high radio frequencies.

“This is a source which is invisible to most of the radio telescopes that we have been using for the last 40 years,” says Melanie Johnston-Hollitt, an astrophysicist at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. “It holds the record for dropping off the fastest” with increasing radio frequency.

Johnston-Hollitt’s colleague Torrance Hodgson, a graduate student at Curtin, discovered the USS Jellyfish while analyzing data from the Murchison Widefield Array, a complex of radio telescopes in Australia that detect low-frequency radio waves. These radio waves are more than a meter long and correspond to photons, particles of light, with the lowest energies. Remarkably, the USS Jellyfish is about 30 times brighter at 87.5 megahertz — a frequency similar to that of an FM radio station — than at 185.5 MHz.

“That is quite spectacular,” says Reinout van Weeren, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands who was not involved with the work. “It is quite a neat result, because this is really extreme.”

The USS Jellyfish bears no relation to previously discovered jellyfish galaxies. “This is absolutely enormous compared to those other things,” Johnston-Hollitt says. Indeed, jellyfish galaxies are a very different kettle of celestial fish. Although they also inhabit galaxy clusters, they are individual galaxies passing through hot gas in a cluster. The hot gas tears the galaxy’s own gas out of it, creating a wake of tentacles. The much larger USS Jellyfish, on the other hand, appears to have formed when intergalactic gas and electrons interacted.

Hodgson and his colleagues note that two galaxies in the Abell 2877 cluster coincide with the brightest patches of radio waves in the USS Jellyfish’s head. These galaxies, the researchers say, probably have supermassive black holes at their centers. The team ran computer simulations and found that the black holes were probably accreting material some 2 billion years ago. As they did so, disks of hot gas formed around each of them, spewing huge jets of material into the surrounding galaxy cluster.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

This ejected material had electrons that whirled around magnetic fields at nearly the speed of light, so the electrons emitted radio waves. Over time, though, the electrons lost energy, and the most energetic electrons, which had been emitting the highest radio frequencies, faded the most. Then a wave of gas sloshed through the entire cluster, reaccelerating the electrons around the two galaxies.

“It’s a very gentle process,” Johnston-Hollitt says. “The electrons don’t get that much energy, which means they don’t light up at high frequencies.” Instead, the gentle gas wave caused electrons to emit radio waves with the lowest energies and frequencies, giving the USS Jellyfish the extreme spectrum it has today.