We may be on the brink of a coronavirus pandemic. Here’s what that means

The virus that causes COVID-19 has now spread to 29 countries

The coronavirus behind COVID-19 continues to spread across the globe. In this image, people wear masks in Piazza Duomo in Milan. Italy has seen over 280 cases of the disease in just a few days.

Sipa USA/AP

Update: On March 11, the World Health Organization announced that it is now calling the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. The story below includes in-depth information on what a pandemic means.

The coronavirus outbreak that began late last year in China has now spread to 29 countries, touching every continent except South America and Antarctica. While the vast majority of cases are still in China, the virus is gaining a foothold in other countries, raising fears the world is on the brink of a pandemic. South Korea has seen nearly 1,000 people sickened just in the last week, while Italian health officials say 229 people nationwide have recently been diagnosed with the disease, now called COVID-19 (SN: 1/29/20).

But who decides what counts as a pandemic, and what does that mean? Here’s what we know so far.

What is a pandemic?

According to the World Health Organization, a pandemic is the worldwide spread of a new disease. It’s most often used in reference to influenza, and generally connotes that an epidemic has spread to two or more continents with sustained, person-to-person transmission.

The severity of illness doesn’t fall under the WHO’s strict definition of a pandemic — just the disease’s spread — though the WHO may take the overall burden of the disease into account before declaring a pandemic. As the top global health agency, the WHO is relied upon to be the first to make the pandemic declaration.

Is COVID-19 a pandemic?

Despite the global reach of the disease, the WHO has so far declined to declare COVID-19 a pandemic.

“For the moment, we are not witnessing the uncontained global spread of this virus, and we are not witnessing large-scale severe death or disease,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a news conference February 24.

“Does this virus have pandemic potential? Absolutely,” Ghebreyesus said. “Are we there yet? From our assessment, not yet.”

When was the last pandemic?

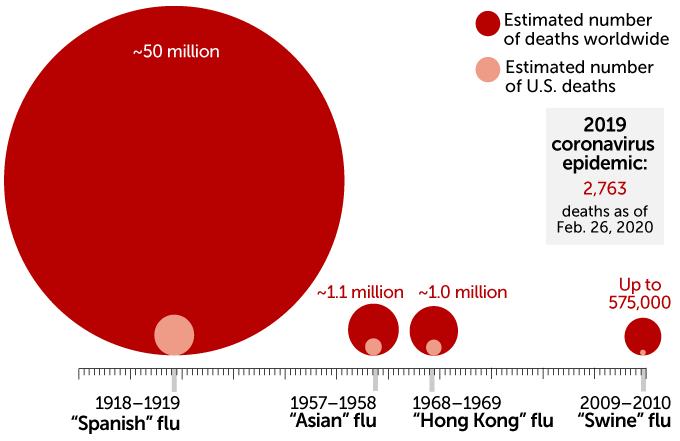

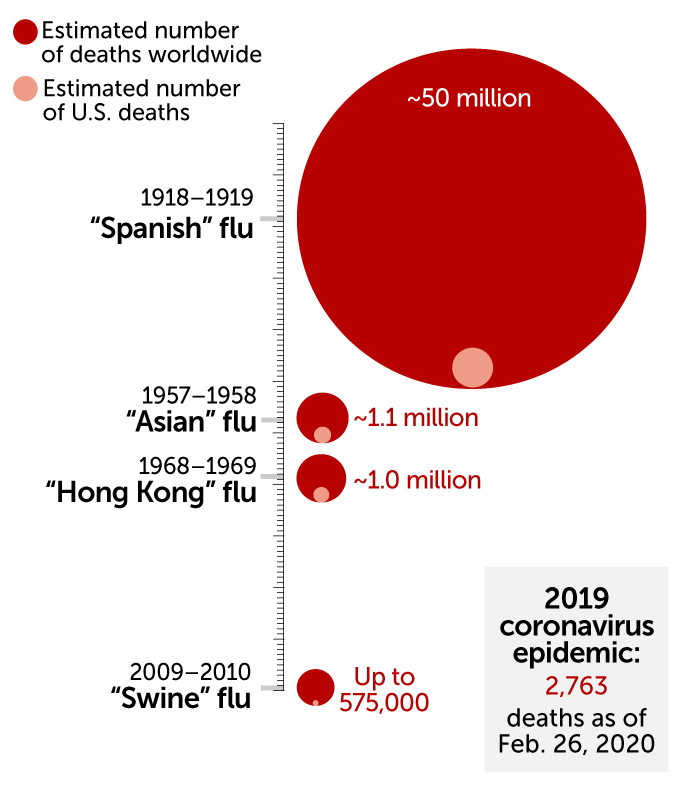

The last time that the WHO declared a pandemic was in 2009, for a then-novel H1N1 strain of influenza, which some researchers estimate infected 1 billion people in the first six months, and killed hundreds of thousands in its first year (SN: 3/26/10). By comparison, over 2,700 people have died from COVID-19 since it emerged in December.

The Spanish Flu of 1918 is the worst pandemic in recent memory; it claimed the lives of at least 50 million people worldwide from 1918 to 1919.

Pandemic history

A pandemic is the global spread of a new disease, according to the WHO. The term is most often used in reference to influenza. Over the last century, there have been four flu pandemics, including the most recent 2009–2010 “swine” or H1N1 pandemic. The deadliest pandemic, which began in 1918, was also caused by an H1N1 virus, of avian origin. Though often popularly called the Spanish flu, there is no consensus on where that virus originated. It’s estimated that the 1918 pandemic caused about 675,000 deaths in the United States.

Estimated number of people killed in flu pandemics, 1900-2010

Source: CDC

How is a pandemic different from an outbreak or epidemic?

All pandemics begin with an outbreak of a new disease in a specific geographic location. If that outbreak becomes larger, but is still confined to a specific region, it becomes an epidemic. At that point, the WHO may declare a public health emergency of international concern to raise awareness that a serious disease is spreading and may affect nearby countries, but ultimately may still be contained. Once a disease spreads globally, with multiple epidemics across different continents, it’s a pandemic.

Exactly when an outbreak crosses the threshold to become a pandemic isn’t entirely clear, according to Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician also at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “There’s not some strict criteria that you check off,” he says. “In some ways, it’s a term of art.”

But when multiple countries across the globe are reporting outbreaks sustained by person-to-person transmission that can no longer be directly tied to the initial source, it’s a pandemic, Adalja says. “I think we’re in the early stages of a pandemic, from an infectious disease physician’s standpoint, and it’s just a matter of time before [the WHO] officially declares it.”

In January, the WHO declared the new coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, or PHEIC, signaling to the global community that COVID-19 was a serious threat (SN: 1/30/20). That declaration allowed WHO to make stronger, though nonbinding, recommendations to member countries in an effort to contain the virus and prevent it from becoming a pandemic.

Declaring a pandemic grants the WHO no additional powers. But it does signal that this virus is no longer containable within a specific region or regions, and that countries may want to shift their focus toward coping with COVID-19 and away from containment measures, such as overly restrictive quarantines.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

What happens if WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic?

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 has reached this point, unlike SARS or MERS, because it spreads much more like the common flu than those more severe, but less transmissible viruses, says Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. “Trying to stop influenza transmission is like trying to stop the wind,” he says. “Containment [of COVID-19] was never going to work.”

Osterholm says that, whether or not the WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic in the coming days, we should all change our mind-set, to shift away from containment toward dealing with a virus that can’t be kept out by travel restrictions. While such measures may temporarily slow the spread of the virus, they’re ineffective in the long term, he says, and can lead to disruptions in the supply chain of medical supplies, much of which is produced in China.

Instead, Osterholm says countries should focus on minimizing the impact of COVID-19. That may be a challenge, since most countries aren’t prepared for a pandemic, according to a study published in late 2019 by the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health Security. After investigating 195 countries, researchers found that most had insufficient systems in place for detecting novel diseases, rapidly moving to contain their spread or caring for the sick. Even the nine most prepared countries, including Canada and the United States, had significant gaps in preparedness.

Osterholm says the first step is to protect health care workers and bolster health care systems for the possible extra burden of treating critical COVID-19 cases, on top of routine cases of flu, heart attacks and cancer diagnoses.

The vast majority of COVID-19 cases will be mild, with some people experiencing no symptoms at all. But experts say identifying individuals who are most at risk for serious complications will help health systems triage resources.

“We’re all gonna get through this,” Osterholm says. “But how we get through this is determined only in part by what the virus does. It’s also a matter of how well we all work together to minimize the impact.”

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.