What we know — and don’t know — about a new virus causing pneumonia in China

There’s little evidence so far of person-to-person transmission, but experts urge vigilance

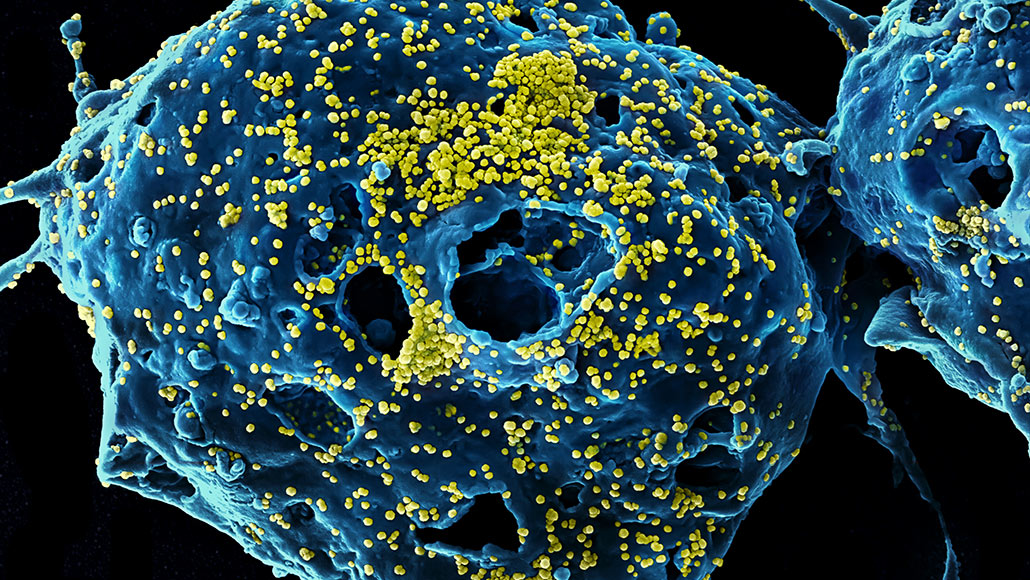

A previously unknown coronavirus is behind an outbreak of respiratory illness in China. So far, there’s little indication the pathogen will spread like a similar virus responsible for MERS (stained yellow in this scanning electron micrograph).

NIAID/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

A mysterious outbreak of pneumonia in central China has preliminarily been pegged to a new coronavirus, but the World Health Organization says there’s no need to panic. Chinese officials have reported little evidence so far of human-to-human transmission, the WHO says, making an epidemic less likely.

Coronaviruses can cause a wide variety of illnesses, from a common cold to the more severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS. A global outbreak of SARS that began in China in 2003 killed 774 people and infected thousands more (SN: 3/26/03). A different coronavirus sparked another deadly outbreak in 2012, with the illness called Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, killing more than 800 people (SN: 7/8/16). Both of those outbreaks began with the virus jumping from animals to humans, and accelerated by spreading among people.

In December, reports emerged of mysterious pneumonia cases in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, with 59 cases confirmed as of January 5. Some patients were vendors at a seafood market selling chicken, bats and other wild animals, raising suspicions of another zoonotic disease. Early tests ruled out viruses associated with SARS, MERS, influenza and other known pathogens.

But the culprit was indeed a coronavirus, one that scientists hadn’t seen before. Chinese investigators identified the new coronavirus from genetic material obtained from one patient, the WHO said in a statement on January 9. Here’s what we know — and what we don’t know — about the new virus.

What do we know so far about this virus?

“We don’t know a whole lot at this point,” says Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. “It seems to be a novel coronavirus that can produce viral pneumonia, which was severe in some cases.”

No deaths have been reported so far from the virus. Doctors will be monitoring how current patients fare, and trying to get a sense of whether the virus impacts people with immune systems that are already vulnerable to better assess the threat from this new virus.

“We don’t [yet] know the ultimate outcome of ongoing cases, or whether those individuals had preexisting conditions,” she says.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

Do we know how this virus is spreading?

Chinese officials say the virus doesn’t readily transmit between humans. While Nuzzo says it’s too soon to know for sure, she agrees that “there doesn’t seem to be evidence of sustained person-to-person transmission. We haven’t seen numbers [of infected] that would make us concerned about that possibility.”

During previous deadly coronavirus outbreaks, health care workers were among the first to get sick as those viruses jumped from human to human, says infectious disease physician Amesh Adalja, also at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “So far, no health care workers or caregivers [who were] not at that fish market have been reported ill, which suggests the virus does not transmit efficiently between humans,” he says.

Still, Adalja doesn’t rule it out as a possibility. Whether the virus is transmissible between people “still needs to be completely determined.”

Should people be worried?

For now, the outbreak seems to be contained, with no new cases reported since December 29. The WHO says it is monitoring the situation, and hasn’t recommended any travel restrictions.

Still, “anytime there’s a novel virus that appears that’s causing critical illness, it merits concern,” Adalja says. “Right now, there’s no cause for panic.”

What are the next steps for public health scientists?

Once the virus’s genetic information is made available, scientists will be able to compare it with other known viruses to see if it’s more closely related to common cold-type triggers or the more deadly varieties that caused SARS or MERS.

But in terms of assessing the threat of this outbreak, “we really need more data,” Adalja says. Experts will be combing through patient histories to determine how severe the illness can become and who might be especially vulnerable. Authorities also will need to be on the lookout for new cases. “It’s important to stay vigilant,” he says.

Both Nuzzo and Adalja hope this outbreak sparks renewed interest in researching coronaviruses and developing vaccines and treatments.

“It’s been 17 years since SARS, and we still don’t have any coronavirus vaccine. We don’t have any coronavirus antivirals,” Adalja says. “The only way we can take outbreaks like these off the table is to develop countermeasures against them.”