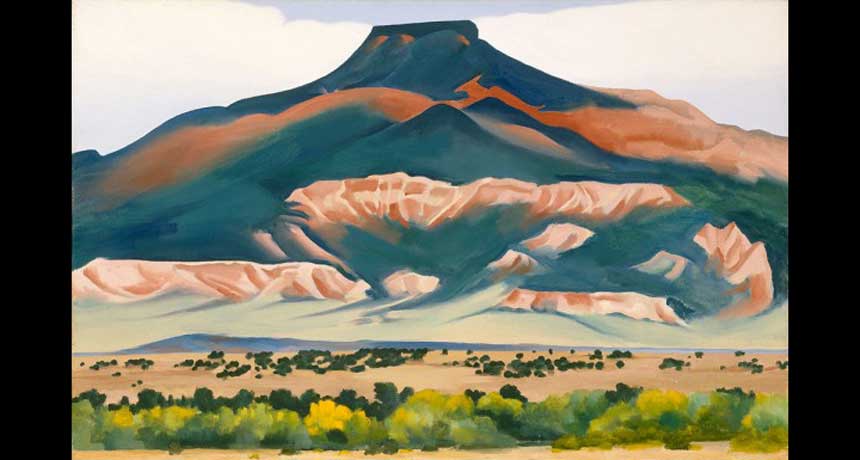

PIMPLED PAINTINGS Many oil paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, including this 1941 work titled “Pedernal,” are slowly being damaged by a type of “acne” forming under the paint.

Georgia O'Keeffe. Pedernal, 1941. Oil on canvas, 19 x 30 1/4 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum [2006.5.172]

WASHINGTON — Like pubescent children, the oil paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe have been breaking out with “acne” as they age, and now scientists know why.

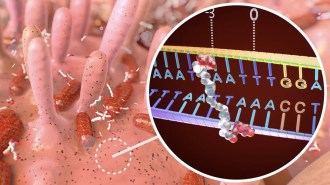

Tiny blisters, which can cause paint to crack and flake off like dry skin, were first spotted forming on the artist’s paintings years ago. O’Keeffe, a key figure in the development of American modern art, herself had noticed these knobs, which at first were dismissed as sand grains kicked up from the artist’s New Mexico desert home and lodged in the oil paint.

Now researchers have identified the true culprit: metal soaps that result from chemical reactions in the paint. The team has also developed a 3-D image capturing computer program, described February 17 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, to help art conservators detect and track these growing “ailments” using only a cell phone or tablet.

O’Keeffe’s works aren’t the first to develop such blisters. Metal soaps, which look a bit like white, microscopic insect eggs, form beneath the surfaces of around 70 percent of all oil paintings, including works by Rembrandt, Francisco de Goya and Vincent van Gogh. “It’s not an unusual phenomenon,” says Marc Walton, a materials scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill.

Scientists in the late 1990s determined that these soaps form when oil paint’s negatively charged fats, which hold the paint’s colored pigments together, react with positively charged metal ions, such as zinc and lead, in the paint. This reaction creates liquid crystals that slowly aggregate beneath a painting’s surface, causing paint layers on the surface to gradually bulge, tear and eventually flake off.

How these crystals combine is unclear. “I wish we had an answer about why that’s occurring,” Walton says, “but it’s still an open research question.”

Medical scan

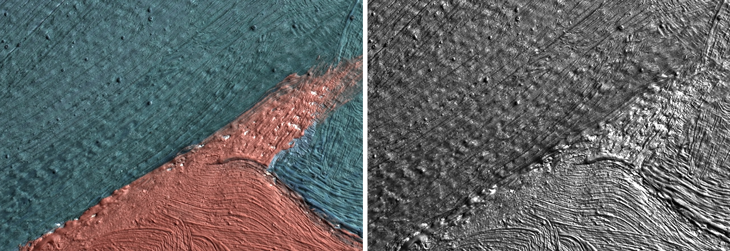

A new computer program can take closeup images of paintings, such as Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1941 painting “Pedernal” (left), and then strip away coloration (right) that can conceal damaging, tell-tale blisters. The program then analyzes the size, distribution and density of the bumps, which can be tracked over time.

For Walton and his colleagues, though, the questions of greater interest are about what factors may lead to crystal formation in the first place, such as relative humidity, light levels or temperature. “To be able to answer those questions, we have to look at it from a macroscopic point of view, and we’ve chosen imaging as a way to get there,” Walton says.

Walton’s colleague at Northwestern, computer scientist Oliver Cossairt, designed a computer program that shines particular patterns of light from a cell phone or tablet’s screen onto a small section of a painting, and then collects the reflected light in the device’s camera.

The program then removes color information, which can camouflage small distortions in the painting’s surface. Using machine learning, the software then distinguishes the knobby structures from other textures such as brushstrokes, and creates a sort of medical report by determining the location, size and density of the blisters.

It’s a bit like Star Trek’s “tricorder,” which could diagnose a human illness simply from a scan, Cossairt says.

The team is currently using this imaging technology to observe test paintings exposed to one of several environmental factors, watching how light, humidity and temperature may affect blisters’ sizes and rates of development.

“You see paintings with this kind of knobby, bubbly surface, and you don’t know if that has happened in five years, 50 years or more,” says art conservation scientist Kenneth Sutherland of the Art Institute of Chicago, who was not part of the research. The new imaging technique “starts to give you a way of monitoring how quickly [the bubbles] are forming and, more specifically, answer questions about what factors are influencing it and how we can control or minimize it.”

Although the technique doesn’t solve the dilemma of soap formation, it provides information that can help in protecting iconic works of art. If new bubbles are forming, for example, an art conservator could perhaps change the environmental conditions where paintings are stored. “Maybe this [process] is just an intrinsic vice, and the real solution is to find the right environment to store the them,” Walton says.