North could be the new south for wintering birds.

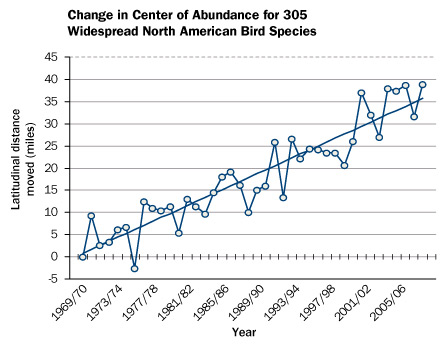

More than half of 305 widespread bird species across North America are spending their winters farther north than they did 40 years ago, says a report released February 10 by the National Audubon Society.

Those shifts dovetail with warming trends in winter temperatures recorded by state during that time, says Audubon scientist Greg Butcher, coauthor of the report. Overall the wintering grounds of the birds have shifted an average of 56 kilometers (35 miles) north in cold months during the past four decades.

Some have moved much more, including red-breasted mergansers (510 kilometers or 317 miles) and purple finches (504 kilometers or 313 miles).

Details of the movement pattern, such as greater shifts in places having more marked temperature changes, suggest climate change is driving the shifts, Butcher says. “We’re showing that global warming isn’t something that’s going to happen far away, say in the Arctic and Antarctic, and it’s not something that might happen in the future,” he says. “It’s something that’s already happened and has been occurring over the last 40 years.”

Woodland birds in the study moved the most, averaging more than a 113-kilometer (70-mile) northward shift in range, more than twice the average change in any other bird group in the study. Not all the species went north. For example, nine of the grassland species moved south, a change that may be attributed to factors beyond temperature.

Butcher and his colleagues drew on data from the Christmas Bird Counts, a 109-year-old tradition in which birders brave whatever winter throws at them to visit predetermined sites where they record all the species they can find during a 24-hour period. In recent years, more than 50,000 volunteers have turned out for the count at some 2,000 locations across the continent.

Such citizen science efforts offer a way to grasp broad trends, says conservation biologist Stuart Butchart of BirdLife International, headquartered in Cambridge, England.

“The strength of this study is that it’s looking at a broad range of species across a large geographic area,” he says. “It’s the overall pattern that’s important and should be raising alarm bells.”

Species that have large ranges may be a good indicator but may not be the birds most at risk from climate change, Butcher says. Species with small, specialized ranges may not have anywhere safe to go. “We’re terribly worried about Hawaiian forest birds,” he says. Warming temperatures allow mosquitoes to rise higher up mountain slopes, carrying avian malaria that has devastated lowland populations.

And even though birds offer a good source of data, other kinds of creatures with even less mobility may be more affected. “Start with trees,” Butcher says. “Trees are big sedentary organisms.” There could be plenty more impacts that don’t get counted every Christmas.