‘Wonderchicken’ is the earliest known modern bird at nearly 67 million years old

The animal is a common ancestor of today’s ducks and chickens

Vertebrate paleontologist Daniel Field of the University of Cambridge holds a 3-D–printed skull of Asteriornis maastrichtensis, which lived 66.7 million years ago and is the earliest known modern bird.

D.J. Field/Univ. of Cambridge

Behold the Wonderchicken, the earliest modern bird ever found.

Asteriornis maastrichtensis lived 66.7 million years ago, less than a million years before the asteroid impact that doomed all nonavian dinosaurs. The winged and beaked descendants of this quail-sized bird, however, survived that mass extinction event, forming a long lineage that includes modern chickens and ducks.

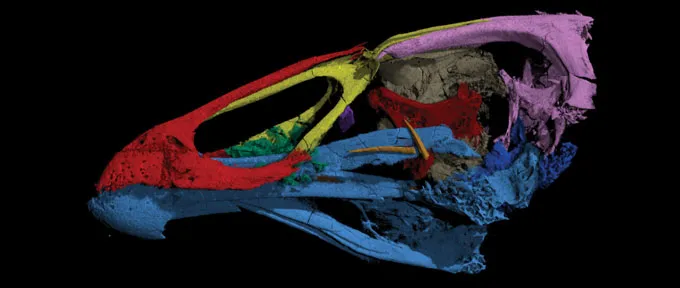

Based on analyses of fossil remains, which consist of a nearly complete skull and a few limb bones, the bird is closely related to the most recent common ancestor of land fowl and waterfowl, researchers report March 18 in Nature.

A. maastrichtensis’ skull is “a never previously seen mashup of ducklike and chickenlike features,” says Daniel Field, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Cambridge. “It’s like a turducken.”

Previous estimates, based on molecular analyses of living bird groups, suggest that modern birds evolved before the mass extinction event roughly 66 million years ago. But this is the first fossil to definitively place a modern ancestor on the scene. The age of the fossil, in fact, suggests that those previous estimates, ranging from 139 million to 89 million years ago, might have overestimated how early these birds arose, Kevin Padian, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley, writes in a commentary in the same issue of Nature.

Modern-type birds share several key traits, such as toothless beaks and fused foot bones. The almost 11,000 living bird species — the paleognaths (flightless birds such as ostriches), anseriformes (waterfowl), galliformes (land fowl) and neoaves (the remaining 95 percent of living bird species) — all share a common ancestor, Field says. “We think that ancestor lived at some time before the end of the Age of Dinosaurs,” he says. But there are very few bird fossils surviving from before the asteroid impact.

The new fossils were discovered in Belgium, in a small rock about the size of a digital camera battery. The rock, made of hardened marine sediments, looked like nothing special from the outside, Field says, just “a few broken bird limb bones poking out.” But any bird bones dating to just before the mass extinction event were intriguing enough that he wanted a closer look.

So Field and his colleagues used computed tomography, a kind of X-ray scanning, to peer inside the rock. And that’s when they saw the skull. The team knew right away they had something special. “The timeline was: See the skull, scream ‘Holy shit,’ give my Ph.D. student a high five, and then start calling it the Wonderchicken.”

The front part of the skull is chickenlike, including the nasal bone that formed part of the nostril, helping to shape its beak. “A barnyard chicken will eat anything you put in front of it,” Field says, and that’s reflected in the chicken’s nonspecialized beak shape. That’s in contrast to other birds, which have beaks clearly specialized for their particular diets — think the tearing bill of a raptor or the long slender sipping beak of a hummingbird.

That beak shape suggests that, like chickens, the ancient bird was also not a picky eater. And that may have been a crucial trait, Field says. “An unspecialized diet is the kind of feature that might have helped animals like the Wonderchicken survive” after the asteroid impact.

But part of the skull is more characteristic of waterfowl like ducks. Those features include a distinctive bone that projects from the back of the skull out to the base of the eye socket and a hooked bone at the back of the jaw. Analyses of the limb bones, meanwhile, suggest that A. maastrichtensis had fairly long legs. The rock containing the fossils consists of marine sediments, suggesting that the bird was a shorebird.

“This is one of the most important bird fossils that has been found in quite some time,” says Stephen Brusatte, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study. “It raises the intriguing possibility that small size and a shoreline habitat may have helped these birds survive the end-Cretaceous extinction” when so many other, larger dinosaurs did not.