WHAT’S IN YOUR LICHEN? A wolf lichen (Letharia vulpina) is one of the species making scientists rethink more than a century of assumptions about what’s in a lichen.

Tim Wheeler

The discovery of unknown yeasts hiding in lichens from six continents could shake up a basic idea of what makes up a lichen partnership.

For more than a century, biologists have described a lichen as a fungus growing intimately with some microbes (algae and/or cyanobacteria) that harvest solar energy. The fungus is treated as so important that its name serves as the name for the whole lichen.

Biologists have recognized that more than one fungus can show up in lichen close-ups, but their role hasn’t been clear. Now that may be on the brink of changing.

Fifty-two genera of lichens collected from around the world include a second fungus — single cells, called yeasts, of a previously unknown order now christened Cyphobasidiales. Toby Spribille of the University of Graz in Austria and colleagues report the finding online July 21 in Science.

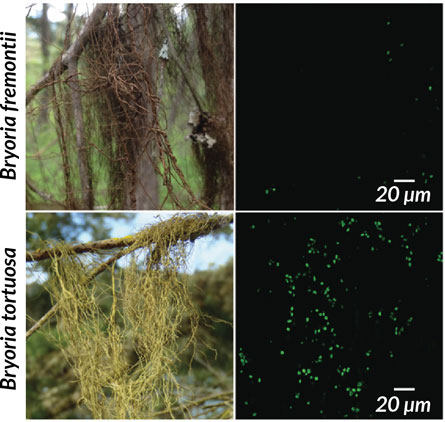

The first example discovered illustrates why these yeasts might turn out to be more than parasites or mere hitchhikers, says study coauthor John McCutcheon of the University of Montana in Missoula. He and Spribille started the research out of curiosity. They wondered how the yellow, toxin-bearing, thready tangles of lichen called Bryoria tortuosa could have the same fungus and the same algal partner — and thus technically be the same species — as the brown, toxin-poor lichen traditionally called B. fremontii. The researchers looked to see which genes were active in each lichen in hopes that some discrepancy could explain the difference in forms. What the researchers found had nothing to do with the alga or previously known fungus. Instead, ample genetic activity of more abundant yeasts in the toxic B. tortuosa turned out to be the most striking disparity.

After five years of work, the research team now has microscope images of yeast cells embedded in the outer layer, or cortex, of B. tortuosa. Gene-activity results suggest that the yeasts could be what’s making the difference between the forms, maybe even synthesizing toxic vulpinic acid. The yeasts turning up across this widespread class of lichens might explain other mysteries, such as why researchers have largely failed to re-create lichen partnerships in the lab.

It’s a bold hypothesis, but lichenologist Robert Lücking of the Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem takes the idea of yeast partners seriously. “This will be a huge surprise to the lichenological and mycological community,” he says.

Editor’s note: This story was updated August 1, 2016, to correct the classification level used to describe the studied lichens.