‘Modern’ humans get an ancient, nonhuman twist

Two new reports suggest that hominids other than Homo sapiens made complex stone tools and fancy necklaces

Unlike science journalists, paleoanthropologists are extremely limited in their source material. While Science News writers and editors could sift through dozens, if not hundreds, of journal articles each week to find science stories worth reporting, those who study the earliest humans and their ancestors must do much with very little: fragments of seashells punctured with holes, shards of carefully, if roughly, cut stone.

This week, two new reports came out on hominids based on such precious finds that, while notable and intriguing, didn’t make the editors’ cut. Instead, they became the topic of this, the first of Deleted Scenes, new blog designed to make readers aware of interesting research that for any of a variety of reasons (not enough time being a prime one) was not covered in the in-depth style Science News prides itself on. —Editors

Behaviors and intellectual capacities that scientists have commonly attributed to the rise of Homo sapiens around 200,000 years ago actually appeared in other Homo species as well, according to a pair of new investigations.

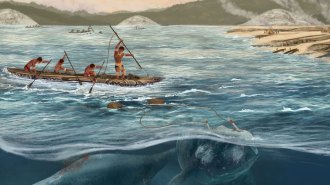

Excavations in Kenya have yielded nearly 100 complete and partial stone blades, along with stones from which blades were struck, dating to 500,000 years ago, say Cara Johnson and Sally McBrearty, both of the University of Connecticut in Storrs. That’s roughly 150,000 years before the earliest previous evidence of blade making. Production of these thin, sharp-edged implements flourished around 30,000 years ago among modern humans. But the mental wherewithal and physical skill to make blades as needed had emerged long before, perhaps in species such as Homo rhodesiensis and Homo erectus, Johnson and McBrearty propose in an upcoming Journal of Human Evolution.

Neither did modern humans have a monopoly on flashy personal ornaments. Discoveries at two 50,000-year-old Spanish sites indicate that Neandertals made necklaces out of seashells dyed with red and yellow pigments. Holes carefully cut out of these shells allowed for their suspension from twine or fiber, say João Zilhão of the University of Bristol, England, and his colleagues. Expanding populations and increasing social complexity among modern humans — not intellectual superiority to Neandertals — led to the widespread production of such ornaments, Zilhão’s team hypothesizes in an upcoming Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.