E is for Effort from Athletes

It takes a lot of energy to move the body–which is why vigorous exercise burns so many calories. However, both exercise and our body’s conversion of food to usable energy can take a physical toll on muscle. Boston researchers now find that supplementing diets with extra vitamin E can reduce not only muscle damage but also biochemically induced stress that ordinarily accompanies heavy exercise.

These findings, from a study of 32 healthy men, are preliminary, notes Jennifer M. Sacheck, a physiologist and nutritionist at the Harvard School of Medicine in Boston. However, she and her colleagues at the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston find evidence that boosting vitamin use benefits both young and old men.

The findings were a surprise, Sacheck says, “because we had thought older men would be more susceptible than younger ones to oxidative stress and muscle damage.” Why? As we age, our ability to mobilize a defense against oxygen’s effect in our bodies gradually diminishes.

It turns out that oxygen is both a blessing and a curse. While essential for stoking many chemical reactions–including those that convert food into energy–this gas can, when unchecked, provoke runaway reactions that damage or kill cells.

Indeed, the body purposefully employs oxidative reactions to cull itself of sick cells and germs. When these reactions have completed their task, the body ordinarily rids itself of the oxidative chemicals–oxidants–by unleashing compounds known as antioxidants. Many of these come from the diet; others are manufactured as needed.

Over time, antioxidant defenses decline in the human body. Either its ability to sense when to turn off the oxidants wanes, or unleashed antioxidants prove too little and too late. What results is an excess oxidation of body tissues, a process that underlies many of the manifestations of aging. These include such chronic disorders as cancer and heart disease.

In New Orleans in late April at the Experimental Biology meeting, Sacheck’s group reported finding that vitamin E–itself a potent antioxidant–helped augment the antioxidant defenses of even young men. However, the effects of that supplement played out differently in the two age groups studied.

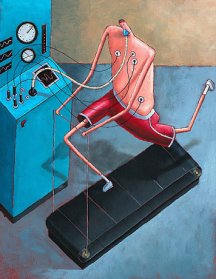

It was all downhill

The Boston scientists recruited men who were relatively fit and had them run downhill on a treadmill for 45 minutes at a stretch. Half were in their 20s; the rest, in their late 60s or early 70s.

In an effort to make the volunteers work comparably hard, the researchers directed each man to run at a speed that caused him to increase his respiration to a particular level, as measured by the researchers.

Explains Sacheck, men running this hard are “a little out of breath. . .where you can speak, but more in fragments than in sentences.” Depending on the fitness of a volunteer, the distance each traveled to achieve this degree of effort varied.

At the start of the experiment and again 3 months later, each man ran at his set pace. Following each session, the researchers measured various indices of muscle injury and biochemical stress.

Between their two runs, the volunteers were randomly assigned to take daily supplements. Half got capsules of soybean oil laced with 1,000 international units (I.U.) of vitamin E (about 45 times the normally recommended daily allowance); others received the soy oil minus this vitamin.

Subsequent analyses turned up different apparent effects of the extra vitamin E in the two age groups.

Among the older men getting the vitamin, the researchers found an improved responsiveness of white blood cells to immune system challenges after exercise. Specifically, blood concentrations of interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6, both agents responsible for controlling inflammation, were roughly 25 percent higher in these men than in older men getting only the soy oil.

Explains Sacheck, that difference suggests that the older men “were able to respond better to [a] toxic stimulus following exercise if they had been given vitamin E.”

In addition, the older vitamin-supplemented men didn’t have as dramatic a rise in an indicator of lipid oxidation during the 3 days following intense exercise as did the unsupplemented men. This apparent protection from oxidation showed up among the supplemented men only after “the extra stress from running.”

Intense exercise usually creates microscopic tears in muscle. These tears not only cause pain but also trigger release of creatine kinase–a muscle enzyme–into blood. Typically, this release peaks about 24 hours after the exercise.

“We found a 30 to 50 percent decline in this among the [supplemented] young men,” compared with the young men getting only soy oil, Sacheck told Science News Online.

That result roughly correlated with the reduced muscle soreness reported by the young men getting extra vitamin E. While supplementation reduced pain, it didn’t eliminate it. “These people were still sore,” Sacheck emphasizes.

When compared with their unsupplemented peers, the older men getting extra vitamin E showed no similar protection against after-exercise muscle damage–either as reduced soreness or diminished creatine kinase. Currently, the scientists are at a loss to explain this result, though clues may emerge when they analyze muscle samples taken from the men after they exercised.

Sometimes it just has to be a pill

Although Sacheck extols deriving nutrients primarily from one’s diet, she notes that getting optimal doses of vitamin E that way can be next to impossible. An ordinary, healthful diet typically offers only 7 to 15 I.U. per day, whereas studies attribute most health benefits from this vitamin to an intake of 200 to 1,000 I.U. per day.

The Harvard scientist plans to extend her study eventually to women. Sacheck excluded them from the first experiment because the body chemistry of pre- and postmenopausal women is very different, making it hard to sort out the biochemical effects of vitamin supplements.

She notes that some scientists consider estrogen–a hormone that diminishes dramatically at menopause–an antioxidant. Its varying concentrations over the course of a woman’s menstrual cycle might therefore mask the magnitude of any benefits due to vitamin E supplementation.

For now, Sacheck doesn’t advise people to stock up on vitamin E capsules–at least not the big-dose ones. After all, because the benefits she recorded showed up only after prolonged, intense exercise, it remains unclear whether couch potatoes would profit similarly from vitamin E.

Moreover, she adds, even athletes may need only a fraction of the amount used in this trial to help their bodies heal after a workout. Indeed, she says, “we see positive responses in immune function at much lower doses–between 200 and 400 I.U. per day.”