Award named for late Science News writer

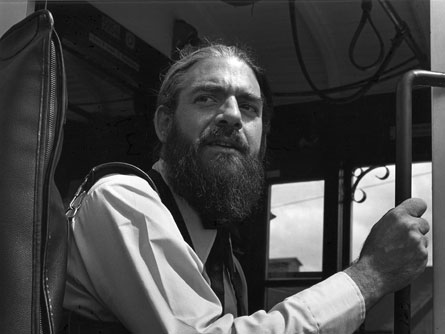

Many Science News subscribers have been devoted readers for decades. If you’re one of them, you’ll remember Jonathan Eberhart’s colorful, detailed and meticulously reported planetary science stories. Hobbled by multiple sclerosis, Jonathan retired in 1991 (and died at age 60, a dozen years later). On Tuesday, the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences presented the first Jonathan Eberhart Planetary Sciences Journalism Award. And it’s hard to imagine a more fitting inaugural recipient than J. Kelly Beatty — Jonathan’s long-time friend, colleague and fellow member of a pickup band.

Beatty won for his May 2008 cover story in Sky & Telescope magazine: “Reunion with Mercury.” It highlights what NASA’s Messenger spacecraft witnessed on its initial flyby earlier in the year — and the questions it raised. His reporting was crisp. Its focus: the science.

I reached Beatty late yesterday at the AAS/DPS meeting in Puerto Rico (from which Jonathan’s successor here, Ron Cowen, has been sending back a series of great news dispatches and blogs). Beatty recalled first meeting his new award’s namesake some 30 years ago. He had just flown down from Sky & Telescope to cover an event at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, outside Washington. “I was just this young puppy dog of a reporter,” he says. And Jonathan took umbrage when he thought the upstart might be attempting to horn in on his tête-à-tête with a scientist, stealing his potential scoop.

But Jonathan soon found Beatty attending the same major news events that he was — sometimes as the only other reporter present — and asking similarly deep, probing questions. In short order, the two forged a deep friendship built on mutual respect.

“Which is why it meant so much for me to get the first one of these awards,” Beatty says. “Because Jonathan and I were cut from the same cloth: For us it was all about the science.”

Although Jonathan was not formally trained in science, researchers did not dismiss this Harvard dropout or even regard him as a reporter. Says Beatty, “They treated him as a colleague” — one who just happened to have this day job writing for Science News. They respected Jonathan’s thoughtful questions, his efforts to get the nuance of some discovery and its interpretation right, and the way he made even complex findings accessible to lay readers.

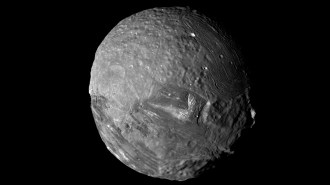

He also took it upon himself to help his fourth-estate colleagues. Beatty recalls one time during a Voyager mission event when hundreds of reporters from all over the world descended on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to cover the jaw-dropping discoveries that were anticipated. “Very few of these reporters knew the background science to the level that Jonathan did. So he arranged to get some of the mission scientists to take time off, prior to the heat of battle, and give us backgrounders.”

These weren’t formal interviews or press briefings, Beatty explains. “They were like: ‘Let’s explore how things work — what it means, for instance, to be a gas-giant atmosphere.’” Later, when scientists announced what the spacecraft had turned up, “These reporters didn’t ask stupid questions in the middle of a press conference, because thanks to Jonathan’s efforts at organizing those events, they now had a context for understanding what they heard.”

Beatty likes to think he’s now carrying on in Jonathan’s footsteps. Actually playing a part in “the circle of science.” Which is to describe what researchers have learned but don’t yet fully understand. Then report what they think might be happening — their hypothesis. And cover whether their suspicions were later confirmed — or shot down.

So what does Beatty miss most about Jonathan’s absence? That’s simple, he says: “The music.”

Those of us who knew Jonathan well remember that he seldom went anywhere without his guitar. He wrote music and performed paying gigs as part of a sea shanty group. Drop by his office and if he wasn’t on the phone with somebody at JPL, he was probably researching just the precise, right word or phrase to incorporate into the lyrics to some new piece, or drafting the liner notes for his next album (yes, he recorded several for Folk-Legacy Records).

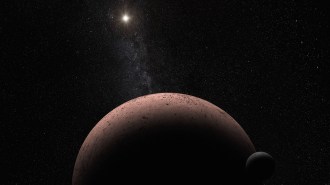

Out at JPL during a Voyager encounter, some scientists started talking about a bright region girdling the midsection of Saturn’s biggest moon. They dubbed it the Titan equatorial band, which Jonathan immediately decided would make a killer name for some rock group. Before long, he and Beatty started jamming together with a number of JPL scientists — as sort of a ragtag pickup band that would reassemble at major planetary-science events.

A JPL photographer memorialized the group in an official lab photo during the 1981 Voyager 2 encounter with Saturn. One evening in Caltech’s Dabney Lounge, after scrounging instruments and renting audio equipment, the band played what would become its only true public performance — on a stage with a real audience.

Beatty (the drummer) remembers what they had been playing when the camera flashed: “Love Portion No. 9.”