Nanosilver disinfects — but at what price?

A broad array of consumer and medical products employ billionths-of-a-meter scale silver particles as embedded disinfectants. A study now suggests that if those nanoparticles get loose and into the body, they might wreak havoc with the human immune system. Documented effects occurred at very low concentrations — levels as minute as parts per trillion or even, sometimes, one-thousandth that much (i.e. parts per quadrillion).

Perturbing immunity could, of course, be very bad.

I ran into the new study on the last day of the Society of Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry’s North America annual meeting in late November. Although one of dozens of studies focusing on potentially toxic impacts of nanoproducts, this study was the only one I encountered that quantified effects on human cells. Its findings, albeit preliminary, reinforce why nanoscale additives should be thoroughly tested before they’re marketed in a way that might let them loose into the environment, much less into our bodies.

When Christopher Perkins and his colleagues at the University of Connecticut’s Center for Environmental Sciences and Engineering learned about new medical tubing that was lined with nanosilver particles, it got them curious where else these tiny silver bits were being employed.

Perkins turned up a website by the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, a program developed by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Pew Charitable Trusts. The site hosts a growing inventory of products relying on nanoparticles. At present, it describes 235 products using nanosilver. These range from toothpastes, pet shampoos, fabric softeners, bath towels, medicines, cosmetics, deodorizers, and baby clothes, to nanosilver-lined baby bottles, refrigerators, food-leftovers containers, and kitchen cutting boards. There were also silver-enhanced electric shavers, curling irons, ankle braces, wrist bands, women’s bras, ATM buttons, and handrails for buses.

Imagine a place you don’t want to see germs breeding and someone has conceived of a nanosilver product to smite those bugs. Most of these novel goods currently seem to be coming out of Asia.

Published studies have also begun describing immune-system impacts of nanosilver. For instance, one preliminary study by researchers in South Korea (home to many nanosilver-products companies) reported last year in International Immunopharmacology that nanosilver particles can alter the production of immune signaling compounds known as cytokines. The authors’ conclusion: “These experimental data suggest that nano-silver could be used to treat immunologic and inflammatory diseases.”

And in a controlled medical setting, that might be true. But what about in an uncontrolled setting — like in your formula-guzzling baby’s stomach, in the pores of skin slathered with silver-enhanced cosmetics or moisturizers, or in the air of a home doused with an odor-combatting silver spray?

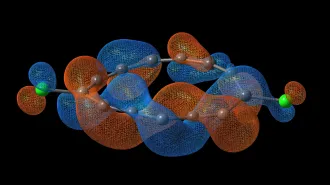

Perkins’ group began pondering whether ingestion or some other internal contact with loosened particles would necessarily be safe, much less beneficial. So they took silver particles that were 10 or 50 nanometers in diameter and incubated them with various types of human cells. Then they quantified “innate” immunity responses — ones that don’t rely on antibodies.

They found that the tinier silver nanoparticles tended to ratchet down the secretion of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, also known as TNF, and of various interleukins such as IL-6. This occurred at the parts-per-quadrillion level. Such cytokine suppression, Perkins says, indicates “your immune system is not operating at peak capacity by any stretch.”

The larger particles? They exhibited almost no effect on cytokines, regardless of the test concentration.

The Connecticut researchers then focused on the ability of immune cells to gobble up foreign bodies for disposal. In their tests, the foreign bodies amounted to tiny naked beads — ones lacking any silver coating. Cells encountered the beads alone or after a three-hour exposure to nanosilver. And the nano-pretreatment at parts per million concentrations increased dramatically the rate at which cells gobbled up the foreign beads.

Is that good or bad? Perkins says it’s hard to know. It’s important that cells can clear out pathogens, which the beads were meant to mimic. However, if cells get overly aggressive in this gobbling behavior, they not only waste precious energy but also risk accidentally trying to eat up healthy cells. Sort of a cannibalism. Clearly, that would not be healthy.

Finally, the researchers measured the ability of cells encountering nanosilver to release a “respiratory burst” of free radicals — chemically reactive molecular fragments that can damage or kill cells. Free radicals are supposed to be deadly: their reason for being is to kill invading germs or sick cells that need to die and be cleared from the body.

Ten-nanometer silver particles increased respiratory bursts at the parts per trillion level, which “is probably bad,” Perkins says. “You’ve got all of these free radicals that have to go somewhere. And they’re pretty nonspecific in what they target. Which means they’ll kill healthy cells as well as bacteria or other pathogens.”

By contrast, the 50 nm silver had less of an effect on free-radical generation, except at relatively high parts per billion concentrations. There they tended to diminish free-radical production.

The take-home message, Perkins says, would appear to be that silver nanoparticles can materially alter immunity, in some instances “taking away the ability for your immune system to deal with pathogens.” That may be an acceptable tradeoff in people who are very sick and for whom the disinfectant properties of nanosilver prove beneficial.

It’s also possible, Perkins points out, that the effects his team is reporting would be smaller in a person. Remember, to date they’ve only been witnessed in a test-tube full of white blood cells or other immune cells.

The proverbial “more work needs to be done” applies, he says. But he emphasizes that the findings by his team and others are too troubling to ignore. Which means more work really does need to be done before anyone can rest assured that nanoparticles are benign.

Unfortunately, an uncontrolled experiment to study those effects is already underway in nations that permit the wholesale production and consumer marketing of nanosilver-enhanced products.