ADHD’s Brain Trail: Cerebral clues emerge for attention disorder

Scientists have identified brain alterations that may underlie attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a psychiatric condition that affects 3 percent to 6 percent of U.S. school children.

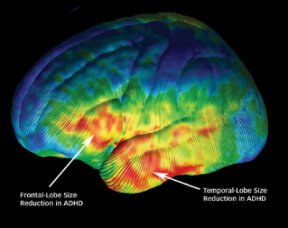

Children and teenagers with ADHD possess less tissue in parts of the brain’s prefrontal and temporal lobes than those without psychiatric disorders do, neurologist Elizabeth R. Sowell of the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine and her coworkers have found. In addition, kids with ADHD display an excessive density of the neuron-rich tissue known as gray matter in regions of cortex toward the back of the brain, the scientists report. The cortex is the brain’s outer layer.

These ADHD-related characteristics all occur within a brain network that, in the research team’s view, regulates attention and controls behavior.

The new findings build on prior evidence that youngsters with ADHD, who lack concentration, self-control, and organizational skills, possess smaller total brain volumes than psychiatrically healthy children do (SN: 10/12/02, p. 227: Attention Loss: ADHD may lower volume of brain).

“We’re now able to localize where brain changes occur that distinguish between kids with and without ADHD,” Sowell says. Her team’s investigation is chronicled in the Nov. 22 Lancet.

The scientists used high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and a new statistical technique to generate maps of average cortical anatomy for 27 youngsters diagnosed with ADHD and 46 others with no psychiatric ailment. Volunteers in both groups ranged in age from 8 to 18. About two-thirds were male.

The study found differences between the groups in brain regions already implicated in the ability to hold separate pieces of information in mind and to maintain visual attention.

It’s not clear why kids with ADHD showed excess gray matter density. The researchers theorize that these children may not develop enough white matter, the axon-rich tissue primarily located below the cortex, thus increasing the relative density of gray matter.

Too few children participated in the new study to enable the researchers to probe for possible brain disparities between boys and girls with ADHD or to rule out possible effects of prescribed-stimulant use on brain anatomy. A 2002 study conducted by another group found no evidence that these medications produce ADHD-relevant brain differences.

The new brain findings may be unique to ADHD’s symptoms, Sowell adds. Different neural patterns have been observed in childhood ailments such as autism and fetal alcohol syndrome, which also include attention and behavior problems.

“Sowell’s study is a step forward,” remarks psychiatrist Jay N. Giedd of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Md. “Still, it’s puzzling and counterintuitive that her group found increased gray matter density in ADHD.”

In other brain studies, Giedd has found smaller cerebellums in kids with ADHD than in their ADHD-free peers. The cerebellum, which lies at the brain’s base and thus wasn’t evaluated by Sowell’s group, integrates sensations and motor functions and has numerous connections to the frontal lobe.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.