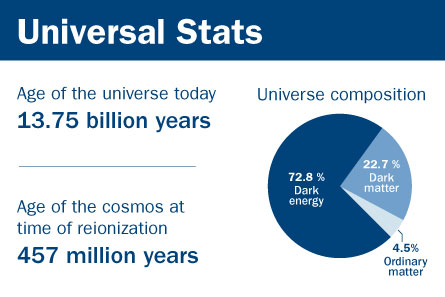

Six papers posted online present new satellite snapshots of the earliest light in the universe. By analyzing these images, cosmologists have made the most accurate determination of the age of the cosmos, have directly detected primordial helium gas for the first time and have discovered a key signature of inflation, the leading model of how the cosmos came to be.

The analysis, based on the first seven years of data taken by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, also provides new evidence that the mysterious entity revving up the expansion of the universe resembles Einstein’s cosmological constant, a factor he inserted but later removed from his theory of general relativity. In addition, the data reveal that theorists don’t have the right model to explain the hot gas that surrounds massive clusters of galaxies.

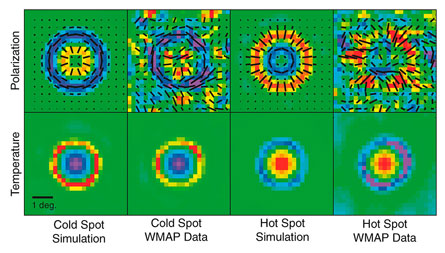

Researchers studying the light, which was generated at the birth of the cosmos but was seen by the satellite as it appeared when it first escaped into space about 400,000 years later, unveiled the findings in six papers posted at arXiv.org online January 26. The ancient light, known as the cosmic microwave background, is peppered with hot and cold spots, signs of the tiny primordial lumps from which galaxies grew.

To calculate the age of the universe, scientists including David Spergel of Princeton University and Charles Bennett of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore compared the size of those hot and cold spots today with the size of the spots when the radiation was first released into space. Using data from WMAP along with studies of distant supernovas and other phenomena, the team finds that the universe is 13.75 billion years old, give or take 0.11 billion. (By comparison, the team’s previous calculation, which used the same method but included only five years of satellite observations, had pegged the universe at 13.73 billion years, plus or minus 0.12 billion.)

Data from the WMAP satellite supports the idea that the early universe inflated rapidly, Bennett says. Inflation theory, which posits that the universe ballooned from subatomic scale to the size of a soccer ball during its first 10-33 seconds, has had great success in explaining the structure of the universe. According to the theory, fluctuations in the intensity of microwave background radiation over larger spatial scales should be slightly bigger than those on smaller scales. The satellite, which was launched in 2001 and will make its last observations this fall, has confirmed that behavior.

“This is a really strong endorsement for the theory,” says Scott Dodelson of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill.

The standard model of cosmology — replete with inflation, invisible material known as dark matter and something called dark energy, which is believed to accelerate cosmic expansion—“is a wild idea,” admits Bennett. But with the newest analysis of the satellite observations “we have confronted the model against the data in a substantially new way… and this picture is holding up very well.”

By using the satellite data to measure the speed of acoustic oscillations — the cosmic equivalent of sound waves — astronomers have confirmed that the early universe forged helium in addition to hydrogen, just as the Big Bang theory has long predicted. Previous studies were based on the amount of helium present in the cosmos’ oldest stars rather than a direct detection of the gas in the early universe.

“This opens up a new window for measuring primordial helium,” Dodelson comments.

The detection “is not a surprise, but it’s nice to have confirmation,” Spergel says.

Researchers also analyzed the satellite data to discern the diversity of neutral elementary particles called neutrinos in the universe. Physicists know of three types—the electron neutrino, the muon neutrino and the tau neutrino. But the current data would be consistent with the existence of either three or four types. The analysis of an additional two years of observations from the satellite may settle whether a fourth type exists, says Bennett.

In a separate finding, WMAP detected the abundance of microwave background photons in the vicinity of galaxy clusters. Here, the satellite has come into conflict with theory. Energetic electrons associated with galaxy clusters are known to interact with some of the microwave background photons, kicking the photons to higher energies than the probe can detect. As a result, the probe ought to record fewer microwave-energy photons in the vicinity of clusters.

The probe indeed records a deficit, but it’s only about half the amount predicted by galaxy cluster theory. The South Pole Telescope, a ground-based experiment that also studies the cosmic microwave background, also finds a lower-than-expected deficit. The mismatch suggests that theorists will have to revise their understanding of galaxy clusters, says Bennett.